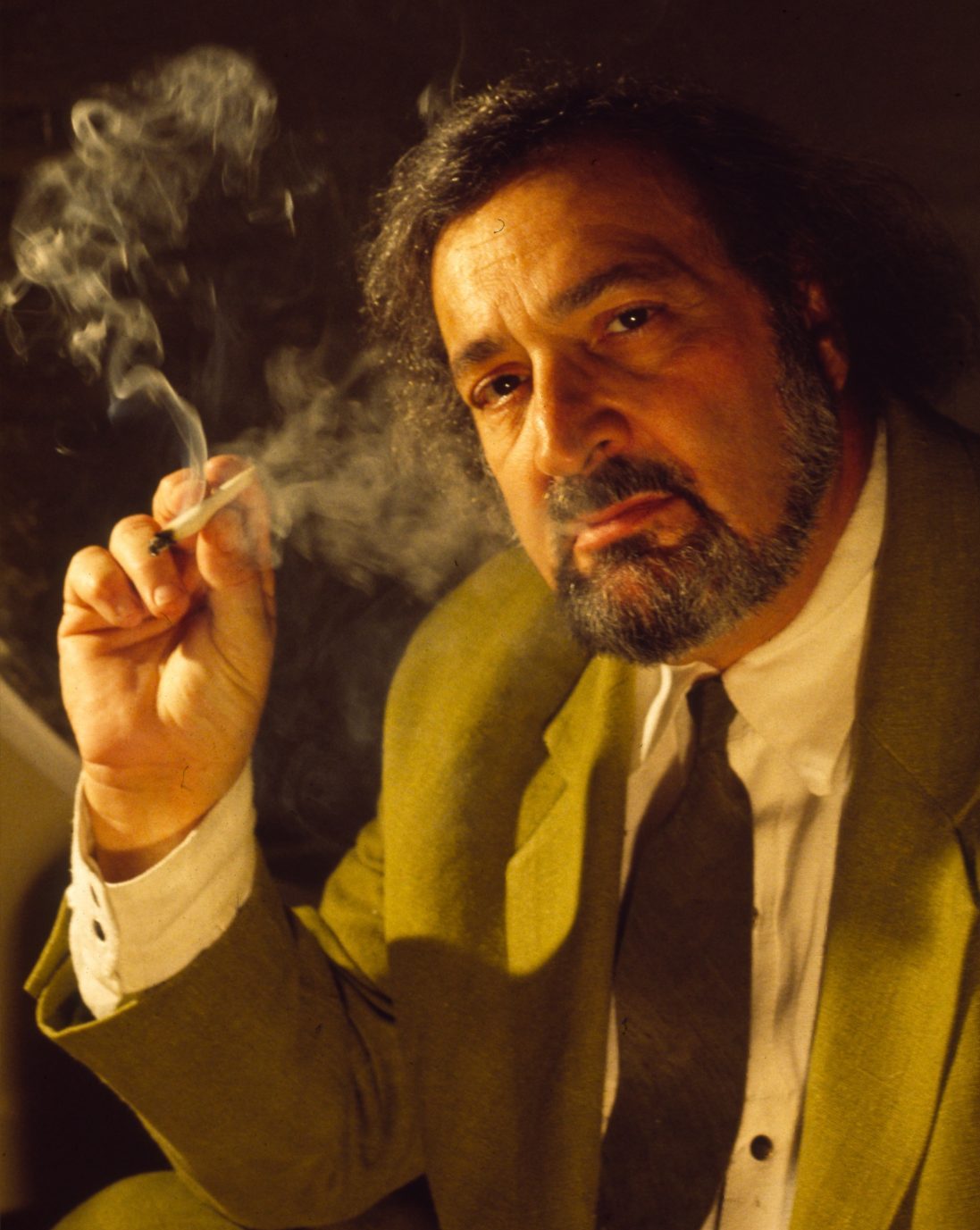

Who was Jack Herer? One of the most celebrated figures in the history of marijuana legalization was not a simple man.

Herer, who died in 2010, would have celebrated his 78th birthday tomorrow. Even before his passing, he became a larger-than-life figure who had a popular strain of cannabis and a prestigious cannabis cultivator/product competition named in his honor.

A former military policeman who didn’t smoke marijuana until he was 30, then a relentless rabble-rouser for cannabis. A Buffalo, New York, native and a West Coast counterculture icon. Married four times and father of six. Author and fearless champion of marijuana legalization. The Hemperor, the Godfather of the Hemp Revolution, the Johnny Appleseed of Weed.

Jack Herer was all that and more.

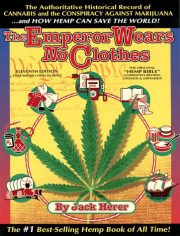

His landmark non-fiction work, “The Emperor Wears No Clothes,” was ground-breaking when it was first published in 1985. The product of years of research, Jack began laying out the book in early 1981 during a brief prison stay for registering voters on federal property after dark. (He was camped out in front of the federal building in L.A., where he and other demonstrators were protesting marijuana laws.) It has provided ammunition for generations of pot advocates and enthusiasts, outlining the history of cannabis, showing its many uses and explaining how it ended up as an illegal substance in the United States.

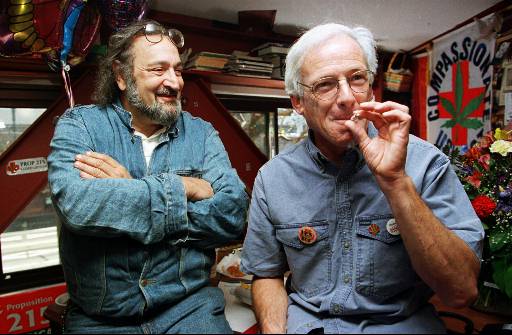

Keith Stroup, the public-interest attorney who founded the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) nearly 50 years ago, first met Herer at cannabis legalization protests and events in the mid-70s. He vividly recalled Herer’s no-concession approach to legalization.

“Occasionally he would come across as a bit abrasive or aggressive because he was upset with NORML, because we had made some compromises and gotten a law passed in some state,” Stroup told The Cannabist. “And Jack inevitably felt it would have been better if we had not passed a law, and held out until we got what he considered a perfect law.”

What really made Herer stand out and attracted people to his message was his unabashed love of marijuana at a time when it was considered a societal evil, Stroup said.

“You couldn’t see (Herer) without recognizing immediately that he was a marijuana aficionado.” Stroup said. “He wore it on his sleeve. So I think a lot of his impact was that he showed the courage to be out front long before it was acceptable to be out front.”

Sometimes at events and protests he would “have more marijuana on him personally than most of us would feel comfortable having in our apartment,” Stroup said. “He would be smoking joints regardless of where he was, handing out joints; he was truly a Johnny Appleseed who appeared to have very little fear of legal repercussions. And that was a helpful trait; it encouraged the movement to come out of the closet.”

For Herer’s children, their dad’s legacy can be bittersweet.

“I think most people in the pot movement kind of know about the (Jack Herer strain of cannabis) but don’t know anything about his legacy,” said Mark Herer, a Portland-based cannabis grower who also ran his father’s famous The Third Eye head shop until its recent closure after 30 years in business. “Of the people who know his book, (few) have read it. It’s disappointing but understandable.”

The Jack Herer strain is just a small part of his dad’s impact on the cannabis legalization movement, Mark said. The people who knew him probably remember Jack Herer as “a crotchety son of a bitch that wouldn’t waver from his goal. And his goal was complete freedom (for cannabis use).”

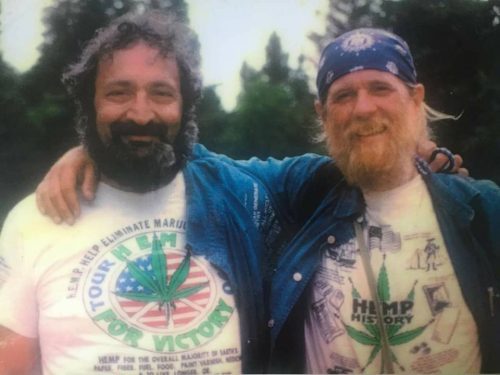

One of the most “radical” things about his father was his willingness to talk publicly about the merits and benefits of cannabis, Mark said, recalling months and months spent touring the country with his father and cohort “Captain” Ed Adair.

“In the fall of ’90 we did this 72-show tour around the East Coast and the Midwest–clocked 15,000 miles,” Mark, now 52, remembered. “We had Captain Ed’s 28-foot motor home, a trailer with all of our gear.”

The caravan stopped in college towns, hit as many festivals as possible and even knocked on doors of private homes to spread the word about marijuana and hemp legalization, he said.

Mark’s brother, Dan Herer, has taken on the mantle of his father’s cannabis activism as director of the Jack Herer Foundation, a hemp educational organization. His father was a “very driven individual” who realized there was a “great void of information and awareness” in society’s understanding of cannabis.

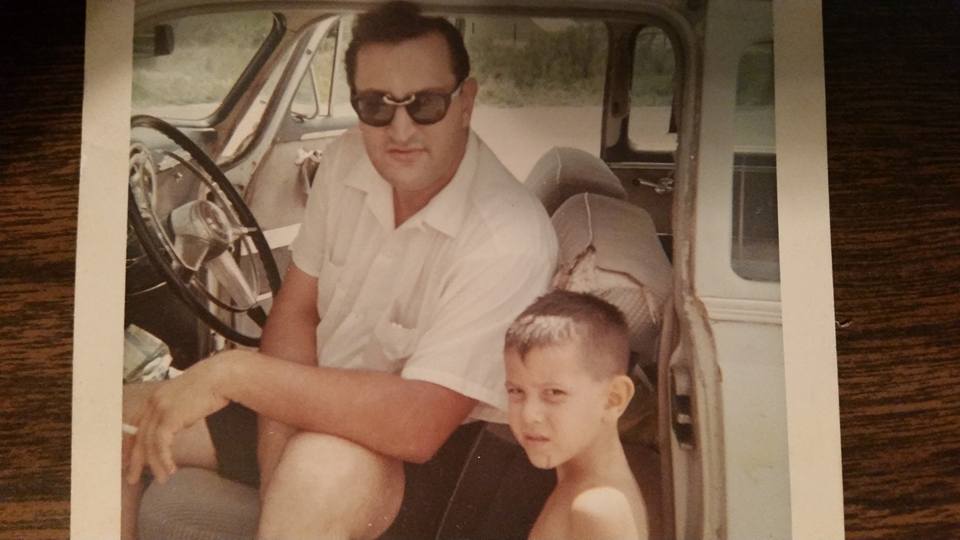

Dan, now 54, has fond memories of taking part in his father’s early 1980s demonstrations at the L.A. federal building.

“As a father-son activity it was an interesting experience,” he told The Cannabist. “Sleeping on the lawn, camped out listening to live rock and roll bands, smoking cannabis on the federal building lawn.”

His father’s posthumous celebrity can be a double-edged sword, Dan said.

“People will say to me ‘I love the (Jack Herer) strain’ but they have no understanding of the man. That cuts deeply,” he said. “When people found out what he stood for, they were able to find their voice (in the legalization movement). But without understanding that, then you don’t know the real story. You don’t know Jack.”

Stroup echoed that sentiment. Today’s audience probably finds it difficult to understand a social and legal environment where smoking marijuana was really considered as dangerous as violent crime, he said.

Back in the 1970s, “getting busted for marijuana was not just an inconvenience that might cause you to lose your job. You were often confronted with the possibility of serving several years in prison–even for a couple of joints,” he said.

Herer was a “phenomenon” and cultural force, Stroup said. He wasn’t a perfect messenger, but he certainly was a courageous messenger.

“I think that myths frequently play a helpful role in social change,” he said. “They allow us to create heroes that help show us the way forward. And the myth of Jack Herer has played that role in the legalization movement.”

Dan Herer said his father was a visionary, who understood the potential of cannabis decades before new technologies allowed the plant’s many applications to be unlocked and exploited.

“When I drive down the street and see a dispensary, or I go to conventions that extol the virtues of this plant in such a wide variety of ways and applications; or when I see the ingenious ways that people are using (cannabis), I see my father every day.”