NEW YORK — Marvin Washington says many of his NFL teammates used cannabis to unwind and ease the pain that inevitably comes from playing America’s most violent game — but it wasn’t for him.

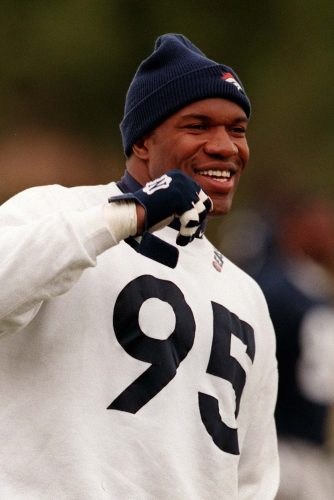

“I hung out with the guys who liked to drink and chase women,” says Washington, a former defensive end who won a Super Bowl ring with the Denver Broncos in 1999. “I knew guys who smoked. But it wasn’t my deal.”

These days, however, marijuana is very much Washington’s deal: The 51-year-old is an entrepreneur with a line of hemp-infused products for athletes. He’s a crusader for the healing powers of cannabis. He’s a leader of a budding movement of former players who are calling on the league and its union to embrace cannabis as a solution to two problems that threaten the future of pro football: traumatic brain injuries and painkiller addiction.

Cannabis has been proven to be effective for managing pain, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has held a patent since 2003 that suggests some non-psychoactive cannabinoids may work as neuroprotectants that could be used to treat Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and other neurological diseases. Washington and other former players — a group that includes Jake Plummer, Eugene Monroe, Leonard Marshall and Jim McMahon — have called on the NFL and its Players Association to fund research into cannabis’ potential as a treatment for long-term brain injuries linked to football, especially chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), the disease linked to the suicides of football stars Junior Seau and Dave Duerson.

“One of my goals is to get cannabis accepted by the athletic community,” says Washington, who was drafted by the New York Jets in the sixth round of the 1989 draft. “The NFL has a safety issue and it needs to look at this plant. The NFL needs to follow the science. I don’t want to kill football, I want to make it safer — with marijuana.”

Washington has interests in four cannabis firms, including Isodiol, a Swiss company that launched a line of hemp-infused sports drinks earlier this year at the NBA All-Star Weekend in New Orleans. Washington says he is using his positions with these companies to provide jobs, investment possibilities and entrepreneurial opportunities for African-Americans and other communities hard hit by America’s decades-long war on drugs.

“I’m not talking about affirmative action,” Washington says. “I’m talking about a level playing field. I don’t want set-asides, I want inclusion.”

Washington is scheduled to moderate a panel at “Cultural Diversity in the Cannabis Industry,” coming up March 31 in New York as part of the Viridian Cannabis Investment Series. Joining him are other former pro athletes from the NFL, NBA and NHL, including Ricky Williams, Cliff Robinson, Dale Davis and Darren McCarty.

Washington has used vaporized cannabidiol (CBD) in the past to ease the aches and pains that have followed him after 11 seasons in the NFL; these days he uses Isodiol’s CBD drops and CBD-infused water to battle muscle soreness and inflammation. He’s also become an unofficial resource for retired NFL players seeking help for chronic pain, depression and other long-term health problems.

“Ex-teammates reach out to me looking for help,” Washington says. “I hear from veterans suffering from PTSD or TBI (traumatic brain injury) — and even my mom and her friends.”

Giving up gridiron for hoops, then back to football

Washington’s life has been rooted in athletics.

He was born in Denver and lived on the city’s northeast side until he was 12 years old, when his family moved to Dallas.

Football wasn’t Washington’s primary sport — he was a standout basketball player who gave up on the gridiron after he enrolled at Dallas’ Kimball High School, where he joined the varsity hoops team as a freshman. He puffed on the joints his friends passed around during his high school days in Texas, but says he wasn’t a fan because marijuana made him anxious and withdrawn.

His skills on the court earned him a basketball scholarship at the University of Texas-El Paso, but he got off track. Washington says he was frustrated by his lack of playing time and spent more time socializing than studying. He was eventually declared academically ineligible.

Washington regained his footing at Hinds Community College in Mississippi, where he not only improved his grades but also joined the football team as a tight end — even though he had not played organized football since the eighth grade.

“The transition was not hard,” Washington says. “I had no bad habits.”

Idaho head basketball coach Tim Floyd, a former UTEP assistant who recruited Washington out of high school, persuaded him to play both hoops and football for the Vandals. He was drafted by the Jets, despite his limited football resume. Team officials told him he was too good of an athlete to pass up.

Washington says roughly 30 to 40 percent of his NFL teammates smoked marijuana and although cannabis is prohibited by the league’s drug policy, coaches and other players rarely called out guys who used weed.

“I never got high with any of my teammates, but I understand why they smoked,” Washington says. “There’s a lot of pressure on football players and it takes off some of that pressure. There’s a lot of pressure to perform and keep your job. A lot of guys are taking care of not just their immediate family but their extended families as well.”

Washington says he enjoyed playing on New York’s big stage for the eight seasons he was with the Jets, although he was also frustrated with the team’s haplessness through much of the ’90s. (The Jets, under coach Rich Kotite, went 3-13 in 1995 and 1-15 in 1996.) Washington was released by the Jets in 1997 and quickly signed with the San Francisco 49ers. He joined the Broncos in 1998 and the team went on to win Super Bowl XXXIII in quarterback John Elway’s last NFL season.

“Denver was a crazy, crazy football town,” Washington says of his season in Colorado. “The Broncos were the defending Super Bowl champions and the fans were crazy. Most of the other players lived in Dove Valley or Englewood, but I lived downtown at 16th and Larimer because I really wanted to immerse myself in Denver.

“Winning the Super Bowl was a big deal for me,” Washington adds. “But the most satisfying game that season was beating the Jets in the AFC Championship Game. I feel like I paid my dues in New York and finally got my reward in Denver.”

Washington pursued a career in finance after he retired from the NFL, but he became involved in the cannabis industry a few years ago after connecting at a golf outing with executives from Kannalife, a Long Island, New York company that is developing cannabis-based drugs the firm claims could help prevent concussions or minimize the damage from head injuries.

Advocating for cannabis research

Washington was intrigued by the industry’s potential for profits, but he also had a personal interest. Like many NFL retirees, Washington was frightened by the research that suggested even mild brain injuries can eventually lead to a lifetime of dementia, depression and other mental health issues — and outraged by allegations that the NFL had covered up that research. Washington says he is in good health, but he’s seen far too many other former NFL players suffer from football-related injuries long after they left the game.

“We knew we might have orthopedic injuries when we left the game,” Washington says. “The league didn’t tell us we could have brain injuries too.”

He co-wrote an op-ed for Huffington Post in January 2015 with fellow NFL retirees Scott Fujita and Brendon Ayanbadejo that urged the league to take the lead on cannabis research. He has also lobbied the NFL Players Association to push for changes in the sport’s drug policies. Those proposals include exemptions for players who live in states where medical or recreational marijuana use is legal, eliminating marijuana screening and doing away with fines and suspensions for marijuana use.

Washington’s behind-the-scenes lobbying may be one reason why the NFLPA announced earlier this year that it will ask team owners — who have to approve any changes to the collectively bargained drug policy — to take a less punitive approach to cannabis.

“I just want people to follow the science,” Washington says. “I don’t want to have a debate with you if you say it is against your ideology or religion. I just want people to follow the science.”