As legal marijuana has proliferated in Denver, city officials concerned about exposure to children long have tried to keep pot shops at least 1,000 feet from schools.

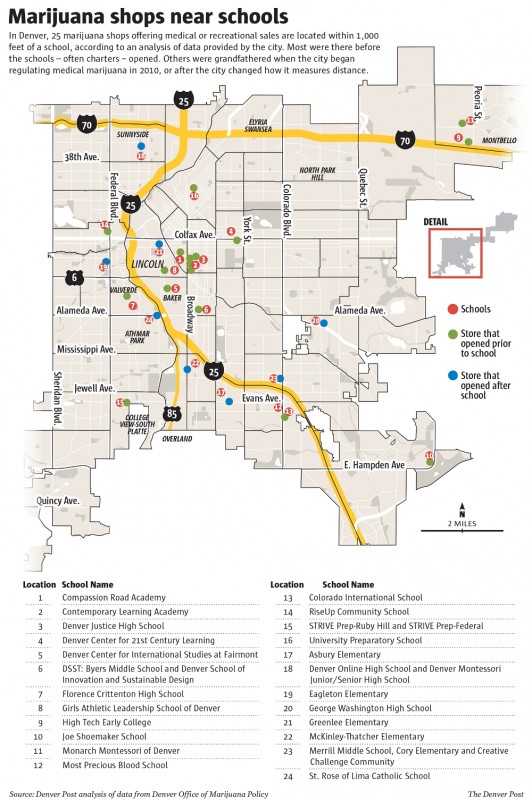

Yet more than two dozen schools in the city now are located closer than that to stores selling medical or recreational marijuana, according to a Denver Post analysis of city data. The Post identified 25 shops closer than 1,000 feet to at least one nearby school, out of 215 medical, recreational or dual marijuana shops.

Most often — in 17 cases — the shops landed there first.

Only later were they joined by new or relocated schools, often charters or alternative schools. Other shops predated city and state distance restrictions or a change in the city’s measuring method.

City officials view all of the shops as effectively grandfathered, putting them on solid legal footing, at least as far as local and state law are concerned. Similarly, the city doesn’t shut down liquor stores or bars when a school later opens within 500 feet, the buffer for liquor licenses.

But the existence of so many marijuana shops near schools has prompted concern among some council members and issue advocates. The issue came to light as the council began considering new restrictions aimed at addressing industry saturation.

“We are making this attractive to kids and young people,” said Gina Carbone, a co-founder of Smart Colorado, a group that advocates for protections for children from marijuana. “The city should do all it can to keep this away from kids,” she said, including taking a hard look at the shops that are near schools.

Just four years ago, before Colorado voters legalized recreational marijuana, U.S. Attorney John Walsh’s office pressured 57 medical marijuana centers across the state to close or move because they were within 1,000 feet of a school. He threatened the possibility of federal prosecution.

For shops near schools now, the hard-to-predict specter of federal intervention still looms.

More on schools and their interaction with marijuana

MMJ in schools: Little by little, schools are opening up to kids’ use of medical marijuana

‘Freaks and Geeks’ meet Steamboat Springs: Teachers design weed curriculum

Weed news and interviews: Get podcasts of The Cannabist Show.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Watch The Cannabist Show.

“That’s something that those businesses have to be aware of — and I know that that’s incredibly difficult,” said Dan Rowland, a spokesman for the city’s marijuana policy office. “… It really is that question of grandfathering (by the city) and of the businesses needing to be aware that they’re operating at risk.”

In a statement to The Post this week, Walsh said the issue remained a concern — “particularly if there is evidence that marijuana is ending up in the hands of young people as a result.” But he said he couldn’t speculate on the potential for future enforcement actions.

City analysts researched the proximity of shops to schools for the council as it considers proposals to replace a temporary moratorium, set to expire May 1, that bars new players from the cannabis industry.

The council is aiming to institute citywide caps on stores and cultivation facilities. A newly drafted proposal spearheaded by at-large member Robin Kniech would allow pending applications for dozens of new business locations to proceed before the city clamps down. A moratorium committee, which has found consensus on some of the components but not all, is expected to consider the measure Monday.

Concerned about odors from grow houses, the council also has discussed making new cultivation facilities follow both the 1,000-foot school buffer that has applied only to new stores and a new 1,000-foot buffer from residential areas.

But as the city’s experience with buffers has shown, it’s not always simple to maintain them.

In 2010, when the city began regulating medical marijuana after the industry already had already taken root, it set 1,000-foot restrictions from schools. And it measured them by the zig-zag distance a pedestrian would travel.

Three years later, when the council set regulations for the coming recreational market, it adopted the same school buffer, but measured as the crow flies — which sets a broader radius. Only in February, when the council updated the city’s marijuana codes, did it finally apply that more restrictive method to new medical shops, too.

While the city’s recent analysis identified 22 shops within 1,000 feet of schools using straight-line measurement, The Post found 25 operating near schools by culling a larger city list.

Among them is Chronorado, a medical marijuana dispensary that opened in early 2010 — just before the city adopted the initial school buffer — on Leetsdale Drive near Monaco Parkway. It is southeast of George Washington High School.

“We haven’t had any trouble with any neighbors — no complaints,” owner Christian Reyes said, and that’s in part because he tries to maintain a clean store image. When students occasionally entered during its first few years, he said the approach was simple: “If you don’t have a red card, you’ve got to get out of here.”

Reyes remembers looking through the mail nervously in 2012, as other licensees near schools received the federal prosecutor’s letters. He never got one. “It was a scary moment for us,” he said.

But if a new license applicant sought to open a store there now, the city would deny it, since it says the store is just short of 800 feet from the high school. In fact, Reyes says the city rejected his recent application to add a retail marijuana license.

For stores that saw schools open nearby, their newfound proximity also might constrain them from something as simple as moving to nicer digs across the street.

Denver attorney Christian Sederberg, who focuses on marijuana law, said shops located near schools don’t appear to be at legal risk.

He noted that there was no specific direction on how far shops should be from schools in a 2013 U.S. Justice Department memo that outlines eight prerogatives states should follow to avoid crackdowns on legalized marijuana sales. Called the “Cole memo,” it simply says the feds are concerned with “preventing the distribution of marijuana to minors.”

“If you look around the country, that 1,000-foot rule does not exist within the federal government,” Sederberg said. “It is not something the federal government is applying uniformly across the country.”

In his statement this week, Walsh said the Cole memo guides his office, but “all of our enforcement decisions are made on a case-by-case basis, taking into account specific circumstances and evidence.”

Compared to 2012, new wrinkles include the city changing how it measures distance and the opening of schools near established marijuana shops.

Often, charter school operators and Denver Public Schools officials have faced few options when seeking new locations.

In recent years, DPS moved two northwest Denver schools, the Contemporary Learning Academy and the Denver Justice High School, to buildings in the 200 and 300 blocks of East Ninth Avenue, respectively, near DPS’ old central office.

Those Capitol Hill locations also were within close proximity to four marijuana shops.

DPS was seeking central locations for CLA, an alternative school for middle- and high-school students, and the Justice High School, a charter school for troubled students.

David Suppes, the district’s chief operating officer, said it would consider nearby marijuana shops in locating a school. But trade-offs sometimes are necessary, especially since marijuana licensees also often seek out central, easily accessible locations.

“We try to find something that is both in the right location where the need is,” he said, “but also in a location that we think would be a good place for kids to learn.”