Justin Henderson was a little gun-shy at first. But it was 2008, and the Great Recession had stalled the real estate industry, leaving the Denver-based developer sitting on properties that weren’t cash-flowing. When a couple of friends and colleagues started leasing their warehouses to pot growers, Henderson weighed his own options. “It’s a tricky thing to tell everybody in your conservative financial life that you’re part of the marijuana industry,” he said.

Henderson now heads a company he believes is poised to become a mover in the cannabis industry beyond Colorado’s borders.

To do so, Henderson’s Peak Marijuana Dispensary, 260 Broadway in Denver, is diversifying — developing a line of marijuana products, acquiring hemp grows, keeping an eye on the implications of health care research — and exploring how to use intellectual property and licensing agreements to expand to other states.

As Colorado’s legal marijuana market matures, these types of prospects are becoming more common. But businesses also are prepping for a future that may include major market corrections and consolidation, and be influenced by legalization in other states.

Nearly two years after retail sales of recreational marijuana became legal in Colorado, the industry shows little sign of slowing.

In August, monthly marijuana sales surpassed the $100 million mark, advancing the yearly total closer to the $1 billion goalpost. The state tallied about 2,000 licenses for marijuana-related businesses, and grow operations have gone from gobbling up metro Denver industrial real estate to filling greenhouses in sun-drenched Pueblo County.

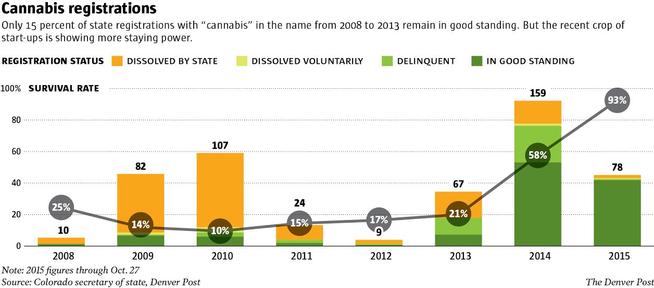

Business formations are down this year from last, but they continue at a strong pace. And compared with the early years of medical marijuana, businesses that are forming seem to be surviving at a higher rate, according to a Denver Post analysis of Colorado Secretary of State records.

Only 15 percent of businesses with the word “cannabis” in their names that registered with the state between 2008 and 2013 remain in good standing.

But nearly 60 percent of cannabis businesses that launched in 2014 are in good standing, as are 93 percent of those formed so far this year.

While it is too soon to know how many of those businesses will survive long-term, the new crop is remaining in good standing at rates above the state average for this year and last.

Colorado’s pot industry hasn’t hit its ceiling, but at some point it will reach a saturation point, said Taylor West, deputy director at the National Cannabis Industry Association.

“I do think people who are looking for something of an early-mover advantage are looking in other states,” she said. “Colorado is not a finished market, but it is certainly a more mature market.”

An initiative to allow the sale of recreational marijuana may land in front of California voters in November 2016, and that could shift the center of gravity from Colorado.

Medical marijuana has deep roots in California, logging about $1.3 billion sales in 2014, or about half of all legal pot sales in the U.S., according to Oakland, Calif.-based ArcView Group’s “The State of Legal Marijuana Markets” report released early this year. ArcView is a cannabis industry research group and investment network.

Nationally, legal marijuana hit about $2.7 billion in sales, up 74 percent from 2013, said Patrick Rea, executive editor of the ArcView report and co-founder and CEO of CanopyBoulder, a startup accelerator for ancillary cannabis businesses.

Inside look at the industry

Enticement for new jobs: Pueblo hemp oil processing plant gets $8 million incentive package

Pot growers’ quest: U.S. patent protection for cannabis seeds

NEW: Get podcasts of The Cannabist Show.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Watch The Cannabist Show.

If California approves recreational pot sales, West and other industry observers project a migration to take place as regulations are developed.

“I think everybody is opening an office in California as quickly as they can,” said Micah Tapman, a partner and program manager of CanopyBoulder. “We are.”

Nathan Mendel, president of Your Green Contractor in Englewood, is among those looking to expand outside of Colorado, using the expertise he developed locally in converting old buildings into grow facilities.

Denver is running out of warehouse space. The next business phase, at least locally, will probably require new greenhouse construction.

Mendel said he has been approached to convert an old potato storage facility in Alamosa and has potential conversions coming together in Massachusetts, Illinois, Washington and Oregon.

Local clients are giving him repeat business, and he will help one develop a grow operation in Nevada, where Mendel plans to open a Las Vegas branch.

Mendel points to signs of a maturing industry. Clients now write checks instead of paying with bags of cash. And although banks still won’t finance buildings, hard money lenders are filling the gap. He said he has yet to be stiffed by a cannabis client.

CanopyBoulder is in the throes of its fall program in which business leaders, investors and industry members help to mentor and build startups.

CanopyBoulder’s 19 portfolio companies have been fairly fundamental to this point — specializing in developing products such as point-of-sale analytics and business-to-business commerce platforms, Tapman said.

As the industry evolves, so will the entrepreneurial activity. And it’s there where Colorado probably will maintain an authoritative position, said Adam Orens, director of the Marijuana Policy Group and BBC Research & Consulting.

“I think Colorado has a great shot at remaining that innovation hub in this cannabis space,” he said. “I think the next few years are very important in cementing that.”

Amendment 64, passed by voters in 2012 , gave Colorado a year to get its regulations in place and begin issuing retail sales licenses.

“The longer it takes California, the better it is for Colorado,” Orens said. “We have strong human capital here.”

Denver software developer Rob Rusher is among those who saw potential in being a first mover. His app, GrowBuddy, replaces paper grow journals. It is free to download, but the data it gathers on what conditions produce what kind of yields for what kind of strains represent a treasure trove.

Growers from around the globe who are using his application are cultivating nearly 12,000 new cannabis plants a month and providing highly detailed records, Rusher said.

After boot-strapping for months, Rusher is now hearing from big corporations that want to partner with him, and he is close to raising his first round of angel financing.

The extent to which the ability to buy and consume pot legally has affected Colorado’s tourism market remains anecdotal at best. Full economic-impact studies are still being conducted.

However, the Colorado Tourism Office says it’s minimal.

About 7 percent of out-of-state travelers visited a marijuana business, according to the tourism office, which cites its own marketing effectiveness research. Only 2 percent of visitors to Colorado are motivated to come to the state because of legal weed.

But some dispensary owners say tourism plays a key role in their businesses.

Peak Marijuana owner Henderson estimates that his store traffic is evenly split between residents and out-of-staters. During the four days surrounding April 20 — the unofficial pot holiday — a total of 82 buses and 17 limos stopped by his central Denver store.

On a normal weekend, about two to three tour buses drop off dozens of patrons at Peak, he said.

Henderson said he knows the novelty may wear off, but he hopes to retain clientele by being “unapologetically top shelf.”

Peak is building out a 10,000-square-foot grow and manufacturing facility for its three product lines: Hush organic pot, Mojo pre-rolled organic joints and Coldwater organic hash.

The company also has bought a 40-acre hemp farm in El Paso County. Henderson sees potential in cultivating hemp for cannabidiol — a valuable, nonpsychoactive chemical compound found in hemp, and its cousin marijuana, that has medical applications.

“We all want to succeed in this industry,” he said. “It’s hard enough to just abide by the rules and regs without every single one of your competitors trying to bury a knife in your spine.”

Colorado’s marijuana industry now is reminiscent of the early days in the natural products and supplements industries, said CanopyBoulder’s Rea.

Both were born out of the counterculture of the 1960s and both have demand driven by consumers seeking an alternative, he said. In the case of marijuana, it’s an alternative to recreational drinking or to pills for medical needs.

But the “irrational enthusiasm” that has led to hundreds of dispensaries and grow operations popping up around the state probably will drive change, he said.

“It’s simple Econ 101: When you have a slower-growing population (and) a fixed market and you increase supply, what happens? Prices go down,” he said. “We’ll see a rapid decline in retail and wholesale operations. I expect a bloodbath when it comes to growers.”

Rea likens the potential correction to what happened to the dietary supplement industry in the mid-1990s. Flush with cash, numerous brands hit the shelves. But after more stable federal regulations were enacted and price cuts were made by giant GNC, companies across the industry lost value.

“I’m waiting for a major player to make a dramatic change in course like that,” Rea said. “It’ll be a bellwether, one of the major players that will cause everybody to gasp.”

Consolidation already is occurring, and some brands are growing in stature: LivWell now has nearly a dozen medical and recreational shops in Colorado.

Grow, grow, grow

Limited options: Pot grows playing pivotal role in tight Denver industrial real estate market

Warren Buffett branching into bud? Company courts Colorado growers with space-saving solutions

Watch: ’60 Minutes Overtime’ explores Colorado pot culture

Review: Are marijuana tours in Colorado worth your time and money?

Watch The Cannabist Show. Follow The Cannabist on Twitter and Facebook

Size has its benefits. However, in a time when regulations are dynamic, chains also can run into barriers, said Michael Elliott, executive director of the Marijuana Industry Group, a Denver-based trade association for the marijuana industry.

“It can be tough getting too big too quick,” Elliott said. “The tax burden can be enormous.”

Aside from the lack of banking, and the fact that federal regulators could flip the switch on the industry in a second, the chief concerns now are drilled deep in the nuances of rules: How is a test conducted? What are the means of testing more efficiently? What can save money?

“We’re down, nose to the grindstone, trying to implement these regulations, trying to cut out the fat,” Elliott said.

How successfully the industry matures in Colorado is critical for the marijuana industry’s future in general, he said.

“We’re being given this window to prove that we can do it in a very safe manner,” he said, “and I think that we’ve proven that we could.”

Alicia Wallace: 303-954-1939, awallace@denverpost.com or @aliciawallace

Staff writer Aldo Svaldi contributed to this report.