State regulators have known since 2012 that marijuana was grown with potentially dangerous pesticides, but pressure from the industry and lack of guidance from federal authorities delayed their efforts to enact regulations, and they ultimately landed on a less restrictive approach than originally envisioned.

Three years of e-mails and records obtained by The Denver Post and dozens of interviews show state regulators struggled with the issue while the cannabis industry protested that proposed limits on pesticides would leave their valuable crops vulnerable to devastating disease.

Last year, as the state was preparing a list of allowable substances that would have restricted pesticides on marijuana to the least toxic chemicals, Colorado Department of Agriculture officials stopped the process under pressure from the industry, The Post found.

“This list has been circulated among marijuana producers and has been met with considerable opposition because of its restrictive nature,” wrote Mitch Yergert, the CDA’s plant industry director, shortly after the April 2014 decision. “There is an inherent conflict with the marijuana growers’ desire to use pesticides other than those” that are least restrictive.

Another year passed before regulators publicly released a draft list of pesticides allowed on marijuana plants — a broader, less restrictive list than initially proposed. That only occurred after the city of Denver began quarantining plants over concerns that pesticides posed a health hazard.

Coverage of marijuana pesticides in Colorado pot

Independent spot-check: Denver Post tests find pesticides in pot products

An alert to consumers and shops: Denver recalls Mahatma pot extracts over unapproved pesticides

Lab results: See the lab results from pot product testing commissioned by The Denver Post

Pot businesses buckle down: Pot industry reacts to new Denver scope on pesticide checks

More debate: Can pesticides be eliminated from commercial marijuana grows?

NEW: Get podcasts of The Cannabist Show.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Watch The Cannabist Show.

The marijuana industry “was the biggest obstacle we had” in devising any effective pesticide regulation, said former Colorado agriculture commissioner John Salazar.

“We were caught between a rock and a hard spot,” he said. “Anything we wanted to allow simply was not enough for that industry.”

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which regulates pesticides, offered the state little advice about what to do because marijuana is an illegal crop under federal law.

“We tried to work with the EPA, to figure out what to do, but we got nothing,” Salazar said.

With little federal guidance and no science to know which pesticides might be safe for consumers, the department made pesticide inspections a low priority, records show.

“Our current policy is to investigate complaints related to MJ (marijuana), otherwise focus on higher priorities,” Laura Quakenbush, the CDA’s pesticide registration coordinator, wrote to a colleague in a December 2012 e-mail.

Critics say the state bowed to industry’s influence.

“Colorado has given the marijuana industry way too much power, way too much control over the political process,” said Kevin Sabet, co-founder of Smart Approaches to Marijuana, a group that opposed legalizing marijuana.

“Regulators are trusting the industry and saying, ‘Show us how to regulate you.’ They’re putting their trust in the industry,” said Samantha Walsh, a lobbyist who has represented marijuana-testing labs and the unions representing workers at cannabis cultivation facilities.

“There’s been foot-dragging in much of the industry,” she said. “It’s a failure of the government to step in and institute these practices.”

State officials say it was important to take into account industry concerns.

“CDA felt there was a need to further explore all possibilities of how best to regulate and identify what pesticides could be legally used on marijuana. During this process, we believe we have identified a better way forward than what we originally proposed in April of 2014,” Yergert told The Post.

Growing marijuana

Not certified: Colorado AG examining pot industry’s use of ‘organic’ term

NEW: Get podcasts of The Cannabist Show.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Watch The Cannabist Show.

The agency is just now preparing for regular inspections of marijuana growers using pesticides, Yergert said, something it already does for other commercial users such as crop-dusting businesses. In July, the CDA began visiting marijuana businesses for “compliance assistance” that focuses on education and training.

And last week, Yergert said, the agency began a new rule-making process to formalize the list of pesticides growers can use.

Heavy-hitting pesticides

Marijuana and pesticides hit CDA’s radar in 2012 when a former employee of the Kine Mine, then a medical marijuana dispensary in Idaho Springs, complained to the state of not being given protective clothing to spray growing plants.

CDA inspectors found two heavy-hitting pesticides — Floramite and Avid — were used on dozens of cannabis plants.

The CDA cited the business with violating a pesticide’s label restrictions. The state was unable to do more because it had not yet determined which pesticides could and could not be used on cannabis in Colorado.

As commercial grow operations spread after recreational pot sale became legal in 2014, complaints continued to flow. Sales of recreational and medical marijuana reached nearly $700 million last year and topped $540 million through July. There are 600 pot-growing licenses in Denver alone.

“I think everyone thought marijuana growers were a bunch of organic growers who would never use pesticides on pot, but that’s definitely not the case,” said Mowgli Holmes, a molecular geneticist at Phylos Bioscience and board member of the Cannabis Safety Institute in Oregon. “A lot of this pesticide use is new and driven by commercial pressures.”

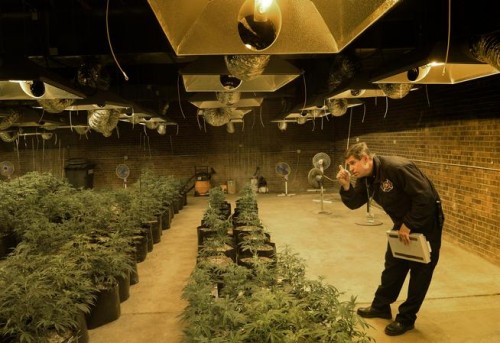

When large numbers of cannabis plants are grown indoors and in close proximity, they are vulnerable to mites and powdery mildews, which can destroy a crop quickly.

To date, there have been 24 inquiries into pesticide complaints involving marijuana businesses, CDA officials said.

Another early complaint came in 2012 when a consumer said a popular cannabis leaf wash for killing bugs claimed to be “99.9999%” water that worked because of an ionic charge.

A state lab found it actually contained high levels of “pyrethrin, a plant-based insecticide that requires EPA registration,” wrote Quakenbush, the CDA’s pesticide registration coordinator.

Officials determined that because the product label did not say that it contained a pesticide, they lacked authority over its use, according to e-mails. The state referred the mislabeling problem to the EPA for investigation, and the state did not look further into the issue.

But the case led state inspectors to send several e-mails to the EPA seeking guidance on how to handle the emerging pesticide problem. Officials also asked whether pesticides allowed on tobacco would suffice. The state received no response, according to e-mails the state provided.

The federal agency responded in an e-mail to The Post that “over the past several years, the U.S. EPA has had interactions with representatives from the Colorado Department of Agriculture on this issue” but provided no details.

Health impact

Colorado initially wanted to do as New Hampshire did, allowing only the least harmful pesticides to be used in marijuana cultivation.

Those included neem, cinnamon and peppermint oils — products so nontoxic that federal registration is not required and no tolerance level is necessary for their residues.

By restricting cannabis growers to those products, Colorado could adapt its rules over time as more information became known about the health impact of chemical residues from pesticides.

Before the sale of recreational pot became legal in 2014, “a majority in the industry’s underground didn’t have very sophisticated practices and were using lots of toxic things they shouldn’t have on a regular basis,” said Devin Liles, who runs The Farm cultivation facility in Boulder.

In April 2014, the CDA laid out the issue: “For food crops, a tolerance (of pesticide residues) must be established. No tolerances have been established for marijuana because they are not recognized as a legal ‘agricultural crop.’ “

Put simply, many pesticides that the marijuana industry was already using — some of them allowed by the EPA on food crops — were to be off the table.

Small, informal working group meetings were held in March and April. Liles said other members of a group on which he participated immediately were worried.

“Some operations were really concerned because what they were using was now on the chopping block,” he said, “and they didn’t know if it would become more restrictive later.”

The proposed rule was published, and a meeting during which stakeholders could speak was scheduled for that May.

“The Colorado Department of Agriculture does not recommend the use of any pesticide not specifically tested, labeled and assigned a set tolerance for use on marijuana because the health effects on consumers are unknown,” the proposed rule said.

Then in late April 2014, soon after CDA issued the proposed rule — and following two meetings where officials heard the industry’s reaction — the agency pulled the plug on its rule-making process.

“The termination will allow the agency more time to meet with the representative group of stakeholders and further review the impacts of the proposed rule,” according to the portion of the Colorado secretary of state’s website where the hearings are tracked.

“We continued to have conversations without having any resolution,” Ron Carleton, CDA’s former deputy commissioner, said in an interview. “The industry was of the opinion they needed the same kind of access to pesticides that other growers were using, that this low-level stuff wouldn’t do it.”

CDA and the marijuana industry continued to wrangle. That June, CDA shared copies of an early, broadened draft list of approved pesticides with at least one industry group.

“The list never meant much because it was always in draft form, never formalized or finalized, and rule-making never occurred,” Michael Elliott, executive director of the Marijuana Industry Group, told The Post in an e-mail.

At a CDA meeting with businesses in December, Elliott said growers were frustrated because they did not believe the state was giving them the tools necessary to fight the problems they faced.

“We need clean product, and we have a huge list of things to test for and failure could literally shut down a business,” he said.

Meanwhile, CDA continued its policy of not checking to see what pesticides marijuana growers were using unless someone complained.

“To date, CDA has not actively sought to inspect and enforce the provisions of the (Colorado) Pesticide Applicator’s Act on marijuana producers,” Yergert, CDA’s plant industry director, wrote in a memo for a meeting in December. The Pesticide Applicator’s Act is the state’s authority to enforce EPA pesticide laws.

The delays had Yergert worried that CDA’s inaction could be problematic.

“The last thing that I want is somebody to get sick and they say it was due to pesticide use” and that the state knew about it, he said at the December meeting with industry representatives. “None of us wants to be in front of that train.”

Turning up the heat

While state regulators and the industry debated how pesticides should be regulated, Denver was about to turn up the heat.

Denver firefighters conducting routine safety inspections of marijuana growhouses in early 2014 discovered some growers were burning sulphur as a fumigant to kill mites. Firefighters say that’s a fire hazard.

Once stopped from using the dangerous substance, the growers turned to pesticides, and firefighters noticed cabinets full of odd-sounding chemicals.

“They will do something to protect these million-dollars worth of plants,” said Lt. Tom Pastorius. “We stopped one issue with the sulphur. But that just led to a whole different issue.”

Regulating marijuana

Denver inspections: City health officials cracking down on pesticide use in pot products

SPECIAL REPORT: 15 months in, edibles safety still concern for Colorado

PTSD lawsuit: Complaint filed against Colorado to allow medical pot for PTSD treatment

NEW: Get podcasts of The Cannabist Show.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Watch The Cannabist Show.

The city’s environmental health department responded by quarantining about 100,000 plants in March after application logs showed pesticides they knew little about. City health officials met with CDA and learned of the agency’s draft list of pesticides it said were OK to use.

The meeting prompted the state to release the list publicly. It was the first time growers say they were fully aware of what they could and could not use.

“At that time, we didn’t want to put the list out,” said John Scott, CDA’s pesticide program manager. “We were still working on the rule itself.”

But once Denver had quarantined the plants, “we felt like it couldn’t wait,” Scott said.

Pesticides on the list have labels so broadly written that the state determined their use on marijuana is permissible. However, CDA also says it does not recommend their use because no one knows whether the pesticides are safe when used on marijuana.

Three of the growers whose plants were quarantined fought back in court, suing the city for allegedly overextending its authority. Pesticides, the businesses argued, were the purview of CDA, not the city.

The industry also turned to the Colorado legislature and had a last-minute amendment designed to stop Denver’s enforcement added to a bill about marijuana tax revenues, according to documents and interviews.

It’s not the only example of marijuana growers looking toward the Capitol for help. Also during the last session, several legislators tried but failed to pass a law that would have removed pesticides entirely from the list of ingredients on marijuana product packages.

The enforcement amendment, which ensured that pesticide oversight of marijuana growers would stay with the state, was tacked on from the Senate floor on the day before it adjourned.

“The worry was that communities could basically ban the use of some pesticides based on emotional responses rather than factual ones,” said Sen. Jerry Sonnenberg, R-Sterling, the amendment’s sponsor. “It was to codify that the state was in charge, not Denver, not any city.”

The impetus for his amendment, Sonnenberg said, came primarily from conversations with three lobbyists who records show are with the Marijuana Industry Group.

Sonnenberg’s re-election committee had accepted about $1,000 in contributions from the three since 2010, according to state campaign finance records. In that time, he’s accepted about $1,800 from all marijuana-related contributors, records show. All contributions Sonnenberg received since 2010 totaled $49,900, according to state filings.

More broadly, the industry has spent at least $421,000 on lobbying on various cannabis-related issues this year, state reports show. In contrast, utility giant Xcel Energy has spent $230,640, according to the company. The city eventually won in court, but the amendment passed as well. Subsequent enforcement actions by Denver occurred at the retail level, far from where plants are actually covered in pesticides and where CDA’s pesticide authority extended.

The city declined to comment on the legislature’s action.

“What was most frustrating about what happened in Denver is that the city went from not participating in the statewide conversation and doing absolutely nothing to placing holds on businesses,” Elliott at MIG said in an interview. “We would have appreciated having them involved in the state process and perhaps having worked out more local solutions instead of coming down quickly with holds.”

Elliott paused, then offered: “That said, I understand why they reacted the way they did. They identified a safety issue and took action. Very little has been going on on this issue on a statewide level.”

Staff writer Joey Bunch contributed to this report.

David Migoya: 303-954-1506, dmigoya@denverpost.com or twitter.com/davidmigoya

Ricardo Baca: 303-954-1394, rbaca@denverpost.com or twitter.com/bruvs