The cups of urine travel by express mail to the Comprehensive Pain Specialists lab in an industrial park in Brentwood, Tenn., not far from Nashville. Most days bring more than 700 of the little sealed cups from clinics across 10 states, wrapped in red-tagged waste bags. The network treats about 48,000 people each month, and many will be tested for drugs.

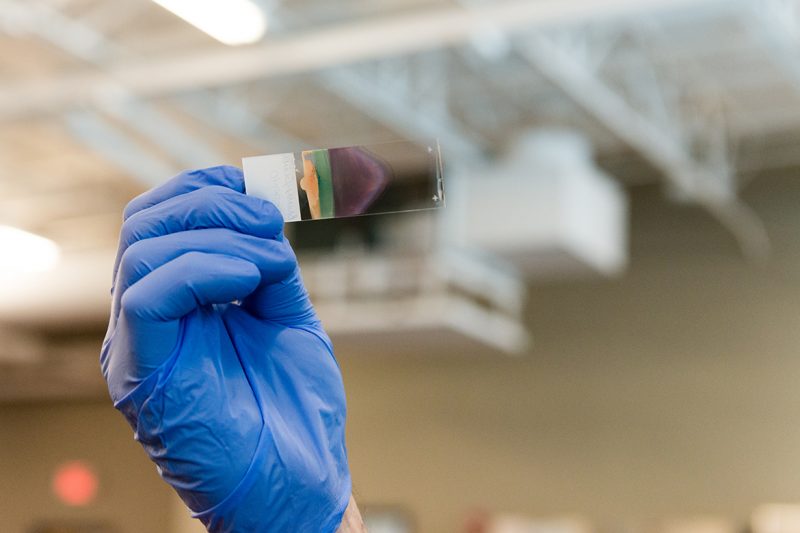

Gloved lab techs keep busy inside the cavernous facility, piping smaller urine samples into tubes. First there are tests to detect opiates that patients have been prescribed by CPS doctors. A second set identifies a wide range of drugs, both legal and illegal, in the urine. The doctors’ orders are displayed on computer screens and tracked by electronic medical records. Test results go back to the clinics in four to five days. The urine ends up stored for a month inside a massive walk-in refrigerator.

The high-tech testing lab’s raw material has become liquid gold for the doctors who own Comprehensive Pain Specialists. This testing process, driven by the nation’s epidemic of painkiller addiction, generates profits across the doctor-owned network of 54 clinics, the largest pain-treatment practice in the Southeast. Medicare paid the company at least $11 million for urine and related tests in 2014, when five of its professionals stood among the nation’s top billers. One nurse practitioner at the company’s clinic in Cleveland, Tenn., single-handedly generated $1.1 million in Medicare billings for urine tests that year, according to Medicare records.

Dr. Peter Kroll, one of the founders of CPS and its medical director, billed Medicare $1.8 million for these drug tests in 2015. He said the costly tests are medically justified to monitor patients on pain pills against risks of addiction or even selling of pills on the black market. “I have to know the medicine is safe and you’re taking it,” Kroll, 46, said in an interview. Kroll said that several states in which CPS is active have high rates of opioid use, which requires more urine testing.

Kaiser Health News, with assistance from researchers at the Mayo Clinic, analyzed available billing data from Medicare and private insurance billing nationwide, and found that spending on urine screens and related genetic tests quadrupled from 2011 to 2014 to an estimated $8.5 billion a year — more than the entire budget of the Environmental Protection Agency. The federal government paid providers more to conduct urine drug tests in 2014 than it spent on the four most recommended cancer screenings combined.

Yet there are virtually no national standards regarding who gets tested, for which drugs and how often. Medicare has spent tens of millions of dollars on tests to detect drugs that presented minimal abuse danger for most patients, according to arguments made by government lawyers in court cases that challenge the standing orders to test patients for drugs. Payments have surged for urine tests for street drugs such as cocaine, PCP and ecstasy, which seldom have been detected in tests done on pain patients. In fact, court records show some of those tests showed up positive just 1 percent of the time.

Urine testing has become particularly lucrative for doctors who operate their own labs. In 2014 and 2015, Medicare paid $1 million or more for drug-related tests billed by health professionals at more than 50 pain management practices across the U.S. At a dozen practices, Medicare billings were twice that high.

Thirty-one pain practitioners received 80 percent or more of their Medicare income just from urine testing, which a federal official called a “red flag” that may signal overuse and could lead to a federal investigation.

“We’re focused on the fact that many physicians are making more money on testing than treating patients,” said Jason Mehta, an assistant U.S. attorney in Jacksonville, Fla. “It is troubling to see providers test everyone for every class of drugs every time they come in.”

“It was almost a license to steal.”

As alarm spread about opioid deaths and overdoses in the past decade, doctors who prescribed the pills were looking for ways to prevent abuse and avert liability. Entrepreneurs saw a lucrative business model: persuade doctors that testing would keep them out of trouble with licensing boards or law enforcement and protect their patients from harm. Some companies offered doctors technical help opening up their own labs.

A 2011 whistleblower lawsuit against one of the nation’s top billers for urine tests, a San Diego-based laboratory owned by Millennium Health LLC, underscores the potential for profit. “Doctor,” one lab representative said during sales calls, according to an affidavit, “drug testing is not about medicine but about making money, and I am going to show you how to make a lot of money.”

Millennium Health, billing records show, took in more than $166 million from Medicare in 2014 despite being the target of at least eight whistleblower cases alleging fraud over the past decade. A Millennium sales manager involved in a 2012 case in Massachusetts reported earning $700,000 in salary and sales commissions in the previous year.

Millennium encouraged doctors to order more tests both as a way to lower patients’ risks and to shield the physicians against possible investigations by law enforcement or medical licensing boards, according to court filings. Millennium denied the allegations in the whistleblower suits and settled all of them with the Justice Department in 2015 by agreeing to pay $256 million; its parent company, Millennium Lab Holdings II, declared bankruptcy.

Tests to detect drugs in urine can be basic and cheap. Doctors have long used testing cups with strips that change color when drugs are present. The cups cost less than $10 each, and a strip can detect 10 types of drugs or more at once and display the results in minutes.

After noticing that some labs were levying huge charges for these simple urine screens, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services moved in April 2010 to limit these billings. To circumvent the new rules, some doctors scrapped cup testing in favor of specialized — and much costlier — tests performed on machines they installed in their facilities. These machines had one major advantage over the cups: Each test for each drug could be billed individually under Medicare rules.

“It was almost a license to steal. You had such a lucrative possibility, it was very tempting to sell as many (tests) as you can,” said Charles Root, a longtime lab industry consultant whose company, CodeMap, has tracked the rise of testing labs in doctors’ offices.

Voluminous Drug Tests

The CPS testing lab in Tennessee opened in 2013, not long before a pain specialist named William Wagner moved from New Mexico to open a CPS clinic in Anderson, S.C. He was lured by the promise of $30,000 a month in salary, which would grow as the clinic added patients and revenue, along with other benefits. His contract said he could be on-site for as little as 20 percent of the clinic’s operating hours.

When the company recruited him, Wagner said, he was told the job offered “potential to earn a great deal of money” from bonuses he would receive from services he generated, including a share of collections from lab services for urine tests done at the new Tennessee facility.

That did not happen, according to Wagner. He is suing CPS, saying that it failed to collect bills for services he rendered and then closed the clinic. CPS refutes Wagner’s claims and says it fulfilled its obligations under the contract. In a counterclaim, CPS argues that Wagner owes it $190,000.

“All of their money was being made off of urine drug screens. They weren’t doing anything else properly,” Wagner said. The lawsuit is pending in federal court in Nashville.

Former CPS chief executive John Davis, in an interview, described the urine-testing lab as part of a “strategic expansion initiative” in which the company invested $6 million to $10 million in computerized equipment and swiftly acquired new clinics. Kroll, one of the owners of CPS, said the idea was to “take the company to the next level.”

Davis, who led the initiative before leaving the company in June, would not discuss the private company’s finances other than to say CPS is profitable and that lab profits “to a great degree” drove the expansion. “Urine screening isn’t the reason why we decided to grow our company. We wanted to help people in need,” Davis said.

Kroll acknowledged that urine tests are profit-makers, but stressed that verifying that patients aren’t abusing drugs gives him a “whole different level of confidence that I’m doing something right for the patients’ condition.”

He said his doctors try to be “judicious” in ordering urine tests. Kroll said some of his doctors and nurses treat “high-risk” patients who require more frequent testing. The company said that its Medicare billing practices, including urine screens, had withstood a “very in-depth” government audit. The audit initially called for repayment of $25 million but was settled in 2016 for less than $7,000, according to the company. Medicare officials had no comment.

Kroll’s orthopedic career took a sharp turn more than a decade ago after watching his brother suffer through multiple surgeries for muscular dystrophy, along with bone fractures, stiffness and pain. His brother died at age 25, and Kroll decided to switch to anesthesiology and become a pain specialist.

“It sensitized me to the plight of people with chronic conditions that we have no medical answer for,” Kroll said. His brother “battled for his whole life.”

Kroll’s career change coincided with a national movement to establish pain management as a vital medical specialty, with its own accrediting societies and lobbying and political arm to advance its interests and those of patients.

Joined by three other doctors, he formed Comprehensive Pain Specialists at a storefront in suburban Hendersonville, Tenn. It quickly gained a foothold on referrals from local doctors unsure, or uneasy, about treating unyielding pain with heavy narcotics such as oxycodone, morphine and methadone.

In 2014, when CPS was among Medicare’s major urine-test billers, Tennessee led the nation in Medicare spending on urine drug tests run by doctors with in-house labs, according to federal billing records.

How much is too much?

There is wide disagreement among legislators, medical trade associations and the state boards that license doctors over the best approach to urine testing. One association of pain specialists argued in 2008 that urine testing could be done as often as weekly, while others have balked at that frequency.

Indiana’s medical board ordered mandatory urine tests for all pain patients in late 2013, only to face a lawsuit from the American Civil Liberties Union, which argued that the policy was unconstitutional and an unlawful search. Officials backed down the next year, and current policy states that testing can be done “at any time the physician determines that it is medically necessary.”

The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, wary of both cost and privacy concerns, declined to set a definitive national standard despite years of debate. In long-awaited guidelines issued in March 2016, the CDC called for testing at the start of opioid therapy and once a year for long-term users. Beyond that, it said, testing should be “left up to the discretion” of the medical professional.

There is likewise little scientific justification for many of these new types of drug testing that have made their way onto doctors’ order sheets and laboratory menus.

Many pain patients on opioids are routinely tested for phencyclidine, an illegal, hallucinogenic drug also known as PCP, or angel dust, Medicare records show. Yet urine tests have rarely detected the drug. Millennium, the San Diego-based company that once topped Medicare billings for urine tests, found PCP in fewer than 1 percent of all patient samples, according to federal court filings.

In a tour of the CPS lab, Chief Operations Officer Jeff Hurst, who has more than two decades of experience working for commercial labs, rattled off a list of drugs ranging from cocaine to heroin and methamphetamine, which he said was “really big in East Tennessee.”

How often urine tests reveal serious drug abuse — or suggest patients might be selling some of their medications instead of taking them — is tough to pin down. Asked during a tour of the laboratory in Tennessee if CPS could provide such data, Hurst said he did not have it; Kroll said he didn’t either.

Hurst said the lab often ends up doing a “long list of tests” because CPS doctors are prescribing dangerous drugs that may be deadly if abused and “need to know what patients are taking.” Prescribed drugs, such as opiates and tranquilizers, are also measured at the CPS lab.

Government officials have criticized the explosive growth in testing for some prescription drugs, notably a class of tranquilizers known as tricyclic antidepressants. Medicare paid more than $45 million in 2014 for more than 200,000 people to be tested for tricyclic drugs, often multiple times. Medicare was billed for 644,495 tests for one tricyclic drug, amitriptyline, up from 6,173 tests five years earlier.

The Department of Justice argued in a 2012 whistleblower case that these tests often couldn’t be justified because of “low abuse potential” of the drugs and a “lack of abuse history for the vast majority of patients.”

When told that drug screens accounted for most of the Medicare income for dozens of pain doctors, federal officials said that was troubling.

“Doctors who receive the lion’s share of their Medicare funds from urine drug testing would certainly raise a red flag,” said Donald White, a spokesman for the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Inspector General. “Confirmation of fraud would require federal investigation and a formal judicial proceeding.”

In a report released last fall, the watchdog office said some uptick in testing might be justified by the drug abuse epidemic, but noted that the situation also “could provide cover for labs that might seek to fraudulently bill Medicare for unnecessary drug testing.”

Medicare pays only for services it considers “medically necessary.” While that sometimes can be a judgment call, pain clinics that adopt a “one-size-fits-all” approach to urine testing may find themselves under suspicion, said Mehta, the assistant U.S. attorney in Florida.

Mehta’s office investigated a network of Florida clinics called Coastal Spine & Pain Center for alleged over-testing, including routinely billing for a second round of expensive tests simply to confirm earlier findings. In a press release in August 2016, the government argued that these tests were “medically unnecessary.” The company paid $7.4 million last year to settle the False Claims Act case. Coastal Spine & Pain, which did not admit fault, had no comment.

Four Coastal Spine & Pain doctors were among the top 50 Medicare billers during 2014, when they charged nearly $6 million for drug tests, according to Medicare billing data analyzed by KHN.

Starting in 2016, Medicare began to crack down on urine billings as part of a federal law that is supposed to reset lab fees for the first time in three decades. Now tougher scrutiny of urine testing, and cuts in reimbursements, may be threatening CPS — or at least its profits.

CPS closed nine clinics last year and told its doctors that urine-testing revenue had dropped off 32 percent in the first quarter of the year, according to a letter then-CEO Davis sent its physician partners.

Davis said the company had to “make some changes” because of cuts in Medicare reimbursements for urine tests and other medical services. A company spokeswoman told KHN that the drop in urine revenue worsened through 2016 but has bounced back somewhat this year.

Despite the cuts, privately held CPS plans to open new clinics this year. Urine testing will remain a key service — for keeping patients safe, it said. CPS is just playing by the rules of the game. “Tell us how often to test,” said Hurst, the operations officer, “and we’ll be happy to follow it.”

The $1,845 Urine Test

(Story continues below video)

Sifting through the data

Kaiser Health News relied on payment data from Medicare’s fee-for-service program, available from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to analyze the prevalence and cost of urine drug testing and related genetic testing. Doctors and laboratories bill Medicare using standard codes. KHN consulted with several billing experts in the field and used government documents to identify relevant billing codes for this analysis.

Medicare reimburses providers for each code they bill based on a standard amount that allows for some geographic variation. Each code represents a type of test, and multiple tests can be done on a single urine sample; therefore, the amount that providers bill for a single sample of urine varies greatly.

Medicare’s Part B payment data is publicly available only for the years 2012 through 2015. KHN acquired historical data from the consulting firm CodeMap going back to 2005 to analyze trends in billing.

KHN also teamed up with researchers at the Mayo Clinic to analyze claims data for private insurers and Medicare Advantage to estimate the total cost per year, which in 2014 was roughly $8.5 billion for private plus government payers. Mayo Clinic researchers accessed data from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse, which includes health insurance claims that cover about 20 million patients per year. The analysis included claims from physicians and independent labs, and excluded any facility (hospital or outpatient) fees. To estimate the yearly cost, KHN took the total cost per enrollee from the Mayo Clinic data analysis and applied it to the estimated populations for both private insurance (from the Current Population Survey) and Medicare Advantage (from CMS’ Beneficiary Public Use File). This is a rough estimate because the OptumLabs claims might not reflect some variations in medical care costs and health conditions across the country.

(Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN’s coverage related to aging & improving care of older adults is supported by The John A. Hartford Foundation.)