The president, a swaggering populist from New York, was worried that a national crisis of opiate addiction was weakening America and diminishing its greatness.

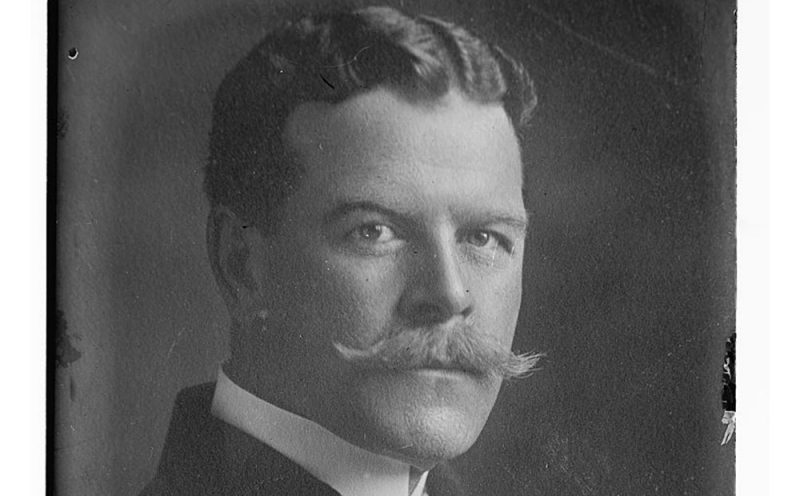

So in 1908, Teddy Roosevelt appointed a handsome Ohio doctor with a handlebar mustache, Hamilton Wright, to be the nation’s first Opium Commissioner.

Americans, Wright warned, “have become the greatest drug fiends in the world.”

The United States developed a pernicious narcotics habit in the decades after the Civil War. Anguished veterans were hooked on morphine. Genteel “society ladies” dosed up with Laudanum – a tincture of alcohol and opium. The wonder drug was widely used as a cough suppressant and it proved very effective at treating diarrhea in children.

Opiates were wickedly addictive, too, and as more and more Americans began abusing them, their control became a cause celebre for Progressive-era reformers like Wright.

“The habit has this nation in its grip to an astonishing extent,” he told the New York Times in 1911. “Our prisons and our hospitals are full of victims of it, it has robbed ten thousand businessmen of moral sense and made them beasts who prey upon their fellows . . . it has become one of the most fertile causes of unhappiness and sin in the United States.”

More than a century later, America has relapsed. The current opioid abuse crisis is more lethal, with record number of fatal overdoses, public health experts note. But it is not the first time in U.S. history that the lax commercialization of legal opioids led to a national epidemic.

The little-known history of America’s first experiment with the narcotic, and the federal government response to it, are today a source of optimism for those who argue that tougher regulation and enforcement can bring the current crisis under control. Faced with a late 19th-century dope scourge, doctors, pharmacists and federal law enforcement officials eventually managed to contain the country’s first addiction epidemic.

“Over the last 150 years of drug use in America, when a problem has emerged, the government has responded,” said DEA official Sean Fearns, the former director of the agency’s small museum on the ground floor of its headquarters near the Pentagon.”I wish we wouldn’t have to keep learning about the dangers of these drugs the hard way,” he said. “But ultimately the turning point comes only when people really begin to see the damage we are doing to our society.”

Lesser waves of opiate abuse, especially heroin, returned several times during the 20th century, especially in large cities, and most notably in the 1970s. But the late 19th century was the only other era in U.S. history that opiate addiction was truly a nationwide crisis, scholars say, afflicting urban and rural areas alike, up and down the country’s social and economic strata.

A brief history of opium

Then as now, it started with drug manufacturers, doctors and pharmacists, not pushers on the street.

The sticky sap of the opium poppy has been relieving pain and getting people high for at least five thousand years. Ancient Sumerians called it “The Joy Plant.” The Egyptians traded opium throughout the Mediterranean, and itinerant Arab merchants probably introduced it to China in the 7th century.

Opium became an engine of human commerce and conquest. English merchants, led by the British East Indian Company – arguably the world’s first modern drug cartel – set up extensive colonial-era opium supply chains to dominate sales in Europe and East Asia. When the Chinese emperors tried to stop them, the British waged the “Opium Wars” of the mid-19th century, occupying Hong Kong to make sure the drug markets remained open.

English poets romanticized the recreational use of the drug, and by the time Thomas De Quincey published “Confessions of an English Opium Eater” in 1821, the British were importing tens of thousands of pounds of it per year.

Historians say it wasn’t until after the American Civil War that the use and abuse of opiates spread widely across the United States. Some of the first addicts were morphine-dependent veterans of the war suffering from all manner of physical and psychological pain, an affliction known as “Soldier’s disease.”

Morphine was invented in the 1820s, but it was the advent of the hypodermic needle that allowed the drug to be injected for the first time. The quick delivery to the bloodstream dramatically intensified the euphoric payload. Soon syringes were being sold through the Sears Roebuck & Co catalogue with DIY drugs vials, according to the DEA’s Fearns.

Around the same time, “you begin to see admonitory literature appear in medical journals saying ‘you need to be careful with this, don’t leave the syringe with the patient,’ ” according to David Courtwright, a leading historian on American drug abuse at the University of North Florida.

For decades, opium, morphine and other narcotics had been the active ingredients in an array of unregulated tinctures and cure-alls sold by neighborhood apothecaries, itinerant peddlers or doctors making house calls.

Just as the contemporary opiate crisis appears to have a gender imbalance – with increasing proportion of women getting hooked – the 19th century addict was typically female and middle-class, according to Courtwright, author of “Dark Paradise: The History of Opiate Addiction in America.” Women were prescribed opiates after childbirth, or to treat “female problems” (menstrual cramps).

Many immigrant workers from China, who were hired to build the railroads, became addicts in labor camps and the tenements of Western cities. The first drug control ordinances in U.S. history were issued in San Francisco in an attempt to stop the spread of “opium dens.”

Then in 1895, German pharmaceuticals giant Bayer came out with a new wonder drug, more powerful than aspirin, that worked phenomenally well as a cough suppressant. Its name was heroisch, meaning strong, or heroic, but in the United States it was marketed under a different brand name: Heroin.

Along with cocaine, it was recommended as a safe alternative to morphine for addicts trying to shake their dependency, and flooded the market in many forms: tinctures, pills, even heroin throat lozenges.

“It possesses many advantages over morphine,” the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal wrote in 1900, advancing claims with a chilling similarity to early advertisements for OxyContin. “It’s not hypnotic, and there’s no danger of acquiring a habit.”

Around that time the specter of the “junkie” and “dope fiend” began to appear as a stigmatized character in lurid newspaper accounts. The early 20th century was also a period of racial anxiety and growing hostility toward immigrants. In their push for a narcotics crackdown, crusaders like Wright, the Opium Commissioner, played to fears that opium-smoking white women would end up trading drugs for sex with Asian men.

“The Temperance Movement wasn’t just alcohol, it was also drugs that were ruining the moral temperament of Americans,” said Lloyd Sederer, the chief medical officer of the New York Office of Mental Health, and the author of a forthcoming book about the current opioid crisis.

The role of the federal government

The U.S. government began taxing opium in 1890, and the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 forced manufacturers to disclose the contents of their products, so consumers wary of the drug would know if it was lurking in their kids’ cough syrup or not. Three years later Congress passed the Opium Exclusion Act, banning its import for the purpose of smoking.

Roosevelt sent Wright to lead an American delegation to the First International Opium Commission in Shanghai in 1909 and another gathering at The Hague in 1912 that produced the first global attempt to regulate narcotics.

Wright continued to push for U.S. legislation over the objections of drug manufacturers, an effort that culminated in the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914. It taxed and tightly regulated the sale and distribution of opium and cocaine-based products, the first broad crackdown in a century of American narcotics prohibition.

Opiates remained available for short-term medical use, but not to maintain addiction, and thousands of doctors and pharmacists were arrested under the Harrison laws, according to Sederer.

A younger generation of physicians viewed opiates far more warily, issuing fewer prescriptions, said Courtwright, and made a crucial difference in the prevention of new addicts.

Prohibition-era gangsters like Arnold Rothstein who trafficked in illegal heroin would become the country’s first drug kingpins in the 1920s, but the number of opiate-addicted Americans would never be as large again.

Until now.

Today

At the peak of the 19th century addiction crisis, roughly 300,000 Americans were probably hooked, according to Courtwright, despite higher estimates by Wright and other activists that were probably inflated. Today, the United States has four times as many people but perhaps 10 times as many addicts.

Moreover, 21st-century dope – especially heroin spiked with synthetic opioids like fentanyl – is more addictive than anything before, according to narcotics experts. The highs are higher, as are the risks of lethal overdose. U.S. law enforcement agents have never had to confront criminal networks as sophisticated and well-financed as the traffickers who dominate narcotics distribution today.

And the flow of America opioids continues today over and under the counter. While new prescriptions for opioid-based drugs peaked in 2011 and have declined slightly, prescribing levels in 2015 were still three times that of 1999, the latest figures show. Dependent Americans who can no longer get the drugs from pharmacies are turning to illegal markets in greater numbers than ever before.

That is the biggest difference between the 19th century crisis and the contemporary one, said Robert Dupont, the former White House drug czar who helped develop the first methadone maintenance programs in 1970s to treat heroin addiction.

Both epidemics began with the over-prescription of pain medication, but today illegal traffickers are far more able to step in as the government cracks down.

“The sea change is the illegal market,” DuPont said. “The move toward synthetic opioids like fentanyl will make everything much harder. The dogs can’t sniff it. You can send it through the mail. It’s very scary.”