The first hint that Damian Farris isn’t your typical farmer is the nickname of his mud-splattered white pickup truck: “Smoked Tofu.”

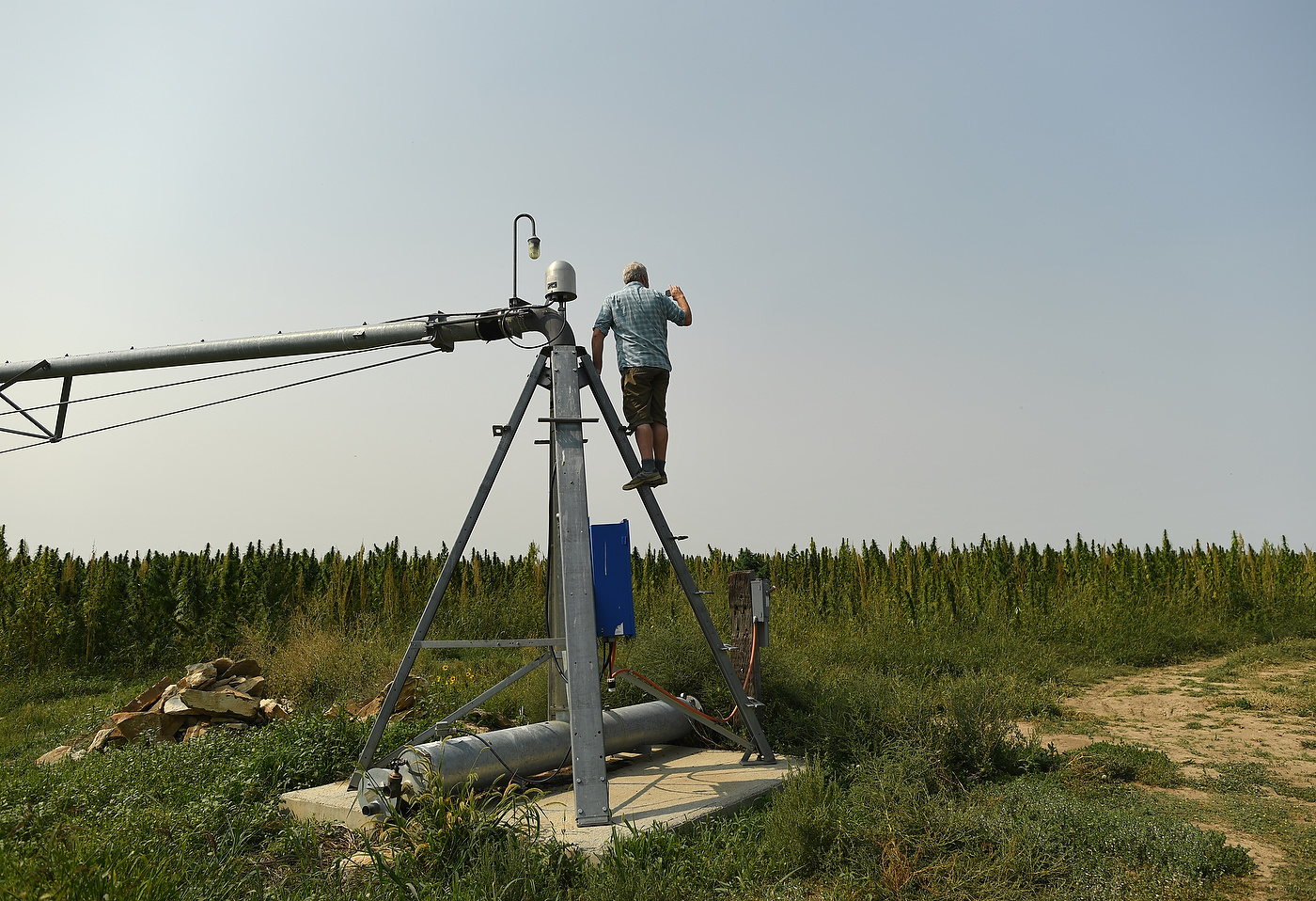

Four years ago he was a hippie with no farming experience and a passion for weed. Now he’s the co-founder of Colorado Cultivars, the self-proclaimed country’s largest hemp farm, just east of Eaton. The marijuana dispensary owner turned industrial hemp grower navigates the farm’s sprawling fields like an old pro.

Since 2014, when the U.S. Farm Bill legalized the growth of industrial hemp in states that regulated the crop, Farris has been part of a rapidly growing industry in Colorado that is bringing farmers and cannabis enthusiasts into business together.

“The first year, people thought we were growing drugs,” Farris said from behind Smoked Tofu’s wheel. “Now farmers are approaching us and asking how they can use hemp in their crop rotation. It’s a big turnaround.”

Hemp doesn’t look like your typical cash crop — it’s less orderly than corn, and grows like skinny Christmas trees in various shades of green. In some places on the Colorado Cultivars farm, the hemp grows so dense it’s impossible to distinguish the rows it was planted in. Elsewhere, its light green stalks commingle with sunflowers.

Industrial hemp is a sturdy crop championed by growers as multifaceted and sustainable. Defined as Cannabis sativa L. plants with less than 0.3 percent tetrahydrocannabinols concentration, or THC, hemp requires less water than corn and can be used to produce cannabidiol (CBD) oil, a nonpsychoactive cannabis compound used for medicinal purposes, and grain for a wide range of commercial items, including food and health products. And its industrial potential is far more wide-ranging: hemp is so strong and lightweight that the auto industry is using it for car parts. It can also be used as construction material in homes, and researchers speculate that hemp biodiesel could one day be used as fuel.

Colorado-grown hemp makes up more than half of U.S. domestic hemp production, said Duane Sinning, assistant director of Colorado Department of Agriculture’s plant industry division, and interest in the crop has grown exponentially since it became legal. The market is worth millions of dollars, but it’s difficult to get a more specific idea of its value because the industry is changing so rapidly and prices fluctuate so quickly, Sinning said.

This year, farms around the state are expected to harvest up to 9,000 acres of hemp, compared with just 200 acres in 2014. The harvest yielded 5,900 acres last year and 2,200 acres in 2015, he said.

But growers looking to cash in on the benefits of growing hemp face a laundry-list of challenges when entering the market: murky federal legality, lack of infrastructure, and uncertainty about American demand for hemp and hemp products. Growers can’t even get crop insurance.

“If you’re a farmer, it’s already risky enough to grow any crop in an emerging industry,” Sinning said. “But if you’re not sure what the market is and you can’t get minimum return if you’re hailed out, that’s really hard for a farmer to swallow all those risks.”

Not only that, hemp growers have been operating without a manual. Dave and Tyler Dyer traditionally grew tomatoes and feed for dairy cattle, but in 2015 they partnered with Colorado Cultivars to grow hemp. This year, the hemp company will harvest 1,250 acres.

“It’s been a challenge,” Tyler Dyer said. “There wasn’t a Hemp for Dummies.”

Hemp, like all forms of Cannabis sativa L., is classified as a Schedule I drug under the Controlled Substances Act, despite past legislative attempts to remove it. This past July, legislators introduced the Industrial Hemp Farming Act of 2017, a bipartisan bill that seeks to remove hemp from the Controlled Substances Act. Without this federal stamp of approval, Colorado farmers growing hemp face barriers to entry that other crops don’t require.

It can be nearly impossible for hemp growers to get a bank account.

Hemp farmer Jim Strang has been unable to get a bank account for Green Acres Hemp Farm, a small operation in southern Colorado he owns with his wife. The Strangs have been cut off from money transfer companies Paypal, Square, and Stripe, and can only accept cash or check for their products — CBD-infused items such as lip balm and lotion.

“It’s been very challenging,” Strang said. “We’re the people who are going to take the brunt of it, since we’re the first in the industry trying to get it going.”

Those who want to export raw hemp material out of Colorado also face concerns about federal regulation, Sinning said. It’s even difficult for farmers growing hemp to secure federal water rights, because the Bureau of Reclamation prohibits such water from being used for federally controlled substances. A Colorado law introduced by state Sen. Don Coram, R-Montrose, and other lawmakers guarantees industrial hemp growers their right to federal water, but until the federal government concurs, Coram said farmers’ water rights are still at risk. U.S. Sens. Michael Bennet and Cory Gardner are cosponsors of a similar bill introduced in July.

“Basically I was encouraging the federal government to get involved,” Coram said, arguing that conflicting state and federal laws create “a lot of uncertainty.”

The Industrial Hemp Farming Act of 2017 has created unlikely allies in lawmakers such as conservative Republican Kentucky congressman James Comer and Colorado’s marijuana-friendly Rep. Jared Polis, a Democrat, who told The Denver Post that he’s hopeful the bill will pass.

“For the first time since I started work on this issue years ago, I’m confident that the finish line is in sight to create new opportunities in industrial hemp for Colorado farmers, processors and consumer product companies,” Polis said via email.

In the meantime, the industry is moving steadily toward more consistency and lower risks for farmers.

When growing hemp became legal in 2014, there were only a few ways to get the seeds. Growers could take seed from feral hemp, left over from a bygone era when the crop was grown around the country for its fiber, to make rope and other items. They could also breed low-THC marijuana, or they could smuggle seeds in from other states. This presented a number of risks for farmers joining the industry, said John McKay, principal investigator at Colorado State University’s McKay Lab in the College of Agricultural Sciences. If a crop had too much THC, it had to be destroyed and it was difficult to know how feral hemp would do once planted, or whether it would grow at all.

Three years down the line, seeds have become more widely available, and more reliable. Around 16 different groups around the state are breeding hemp, responding to the boom in interest in the crop by farmers and investors, Duane Sinning said.

He expects Colorado Department of Agriculture-approved certified hemp seeds to be on the market by 2018.

As the industry continues to expand, the next big question is how much demand there is for the crop.

“Most farmers, whatever they’re growing, they’ve been growing for 40 years and there’s no mystery to it,” McKay said. “Where are they going to drive their truck to at the end of the season? Who’s going to buy it? They can plant soybeans under contract, and know who’s going to buy it. That’s not the case with hemp.”