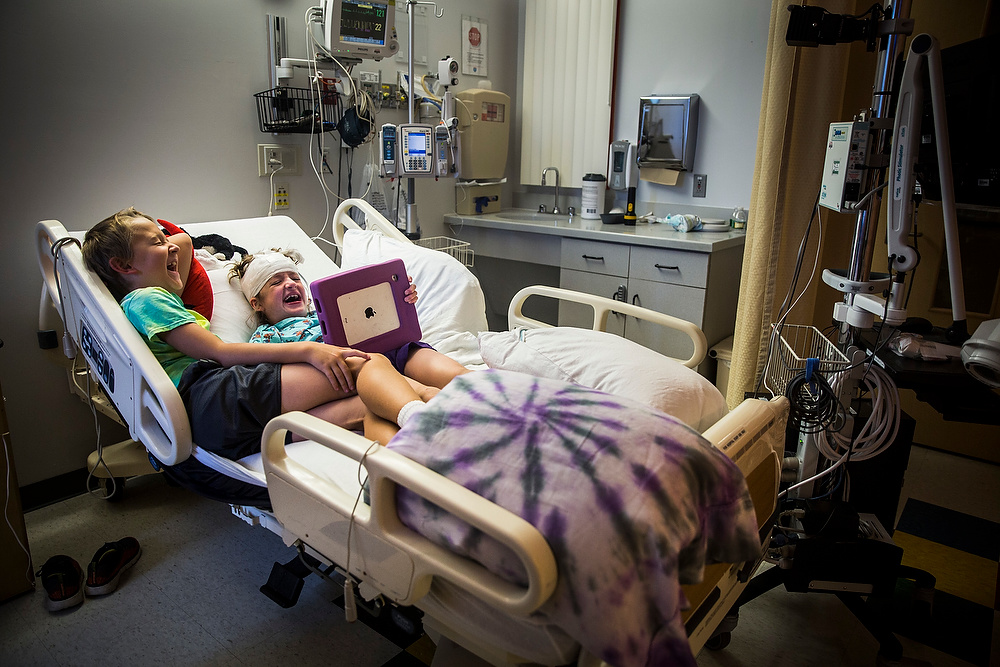

HARTFORD, Conn. — There are good days for West Tarricone. Days when she can laugh and live like any other 9-year-old. Days when she can play with her brother, Blake, and watch “The Ellen DeGeneres Show” on her iPad.

But there are also bad days. Days when her body weathers 100 seizures. Days when it has closer to 1,000 — some lasting more than 90 minutes.

Lately, she’s been having more good days thanks to Connecticut’s new experiment with medical marijuana.

Doctors diagnosed West just after her first birthday, not long after her mother Cara Tarricone noticed she had been jerking oddly. Two weeks before they learned West had intractable epilepsy, she had a grand mal seizure.

In the years since, West has tried a battery of nearly two dozen medicines, but just one has brought her some comfort — cannabis oil, which is derived from the marijuana plant.

Medical marijuana

“Without it, we’d be in the hospital, we’d just live there because we’d have to be controlling bigger seizures all the time,” Tarricone said.

West takes the cannabis oil daily, in addition to four pharmaceutical medications. Tarricone says she’s “pleased” with the daily medication, and has seen a decrease in some seizure activity.

But the medicine’s most profound effect comes when West’s seizures flare beyond control. When that occurs, Tarricone rubs a different concentration of the oil into her daughter’s gums as a “rescue medicine.” Within a minute, the more intense symptoms subside. Her tightened muscles slacken. Her breathing regulates.

Before the oil, the family had to rely on pharmaceutical rescue medicines. When they didn’t show signs of working right away, Tarricone would have to call for an ambulance.

During intense seizures, they usually didn’t work.

“I said immediately, this is a natural option, and I want this for my child,” Tarricone said. “Something that could eliminate a lot of extra pharmaceutical medication in her system and be so simple and straightforward? This is something we needed for our daughter.”

The state legislature passed a bill approving cannabis as a palliative treatment for childhood seizure patients in May 2016, but the medicine didn’t become available until October, when the law went into effect.

The Tarricones received their first batch for West in March. She is currently one of less than 50 children in Connecticut utilizing the medicine, according to the state Department of Consumer Protection.

Getting the medicine was a victory for the family, one of the more vocal advocates for legalizing cannabis oil.

And as they begin using it, they hope their story inspires a greater understanding and wider acceptance of a substance that could improve the lives of other children.

Fighting for medicine

West’s condition is so unstable that Tarricone had to give up her job to care for the girl. Her wife, Diane, works three jobs to support the family.

Moving to another state, like California, where medical marijuana is more readily available, was not an option. Their son, for one, couldn’t bear the thought of leaving his friends and school, she said.

Besides, the Tarricones are attached to their neurologist at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Dr. Jennifer Madan Cohen.

Attached to the point where leaving her care was a risk they wouldn’t take. So if they couldn’t go to the drug, they’d find a way to bring it to them.

Tarricone lent her voice to the movement of parents seeking medical marijuana for their children. It was a fledgling group in 2015, when the first bill failed in the state legislature.

But a year later, they were ready, Tarricone said, adding their testimony to a groundswell of support for the legislation.

“We shared stories and made it personal, how it would affect us, how it would affect our children,” she said. “I truly think that gave us the momentum. In that year, we had enough opportunity to educate legislators personally as to what the medication is, how it worked, how effective it could be, and that parents should really be the ones making that decision with their medical care providers.”

But when they initially broached the subject with Madan Cohen and the other members of West’s medical team, they were somewhat skeptical, Tarricone said.

“They just didn’t know that this was something parents were pursuing, and moving to other states to pursue,” she said. “But I kept saying, ‘This is what’s happening, let’s talk about this more, I want to continue this conversation.'”

“And I didn’t let it go,” she added.

Special Report: CBD in Colorado

Madan Cohen has treated West since her diagnosis. In that time, she’s seen her try a bevy of medicines for the seizures that plague her.

“You name it, she’s been on it,” Madan Cohen, the medical director of the hospital’s epilepsy center and clinical neurophysiology lab, said in her office recently. “If there’s a medicine I’ve had, she’s tried it.”

Because of that, she doesn’t see the Tarricones’ interest in medical marijuana as “irrational.”

“They’ve seen their child have pretty severe seizures and not have control with the various treatments they have,” she said. “So I’ve never discouraged a family’s want to try this treatment, but we have to decide when it’s the right time to try something.”

She acknowledged that West was at a point in her life where trying medical marijuana was an attractive option.

But when it comes to the treatment’s effectiveness, Madan Cohen is unable to give a definite answer. And it’s not just because the utilization of the oil is still relatively new for the adolescent.

Trials and error

Medical marijuana is unique in the way it’s dispensed. Normally, medication requires FDA approval before it can be prescribed to patients. However, because individual states are legalizing marijuana for medicinal purposes, patients seeking the drug are circumventing that approval process, receiving a substance that the federal government considers illegal — and largely untested as a drug.

Still, within the medical community, there’s a body of evidence supporting the benefits of using cannabidiol, a chemical compound found in marijuana, in treating seizures. Evidence like clinical trials sponsored by pharmaceutical companies with deep pockets. Madan Cohen herself is involved in one such trial, the goal of which is to accumulate enough evidence to one day seek FDA approval.

But the products available in Connecticut are not purely cannabidiol. They also contain tetrahydrocannabinol, another chemical component found in marijuana known to be psychoactive, in various concentrations.

Trials studying the effectiveness of THC, or any other component of marijuana, can be difficult to get clearance for, according to Dr. William Zempsky, a pediatrician with Connecticut Children’s Medical Center who sits on the board of physicians for the state’s medical marijuana program.

For one, limited availability means that different physicians work with different strains of the plant. And there seem to be multiple variants for every study: how the marijuana is consumed and the conditions it’s used to treat, for example.

“We’re dealing with a different combination of drugs that people study,” Zempsky said. “It’s really hard to take all that information and go forth and say ‘Medical marijuana works for x condition,’ because we’re not talking about the same thing, and to drill it down to an individual patient is more complex.”

Connecticut has a history of such studies. St. Francis Hospital and Medical Center sought to study marijuana as an alternative to opioid painkillers. Yale University has sponsored similar trials in the past, according to Zempsky.

And Connecticut Children’s is laying the groundwork for a study of its own, using data from its patients to see the long-term effects of medical marijuana.

The medications that West uses, for example, are low doses of THC. Just enough to treat her seizures and keep her comfortable.

The family initially tried cannabidiol medication, Tarricone said. It made West’s seizures even worse.

Still, THC’s effectiveness hasn’t been proven clinically, Madan Cohen said. Instead, physicians rely on anecdotal evidence, like the Tarricones’ positive experience, when informing prospective patients.

“I think there’s enough people who reported it that that’s some level of data,” Madan Cohen said. “But it’s just not the same level of data as a randomized, controlled trial and the things the FDA requires to get a medicine approved as a treatment.”

Trials help determine crucial medical information, like the drug’s side effects, dosing recommendations and interactions with other medicines.

Without them, physicians treating patients with medical marijuana have to undergo some trial and error, seeing what works best in their individual case.

“My advice to parents — and this is what I told West’s parents as well — is that you have to think of it as you’re doing your own clinical trial on your child,” she said. “We don’t know what the outcome is going to be, we don’t know if they’re going to respond, we don’t know what the side effects are.

“But there are some families who feel that risk is acceptable compared to what is going on in the child’s life medically at the current time,” she added.

A family’s choice

FDA approval would have the additional benefit of making the medicine more affordable: All approved drugs have to be covered at least partially by medical insurance.

If for no other reason than that, Madan Cohen is encouraging more trials, more testing from policymakers both here and in Washington.

“Now, people are desperate, and they feel like the government is just getting in their way, as opposed to the idea that the government is protecting them from potential harm,” she said. “And I think the intentions are good to make sure that something doesn’t have a lot of side effects.”

Zempsky said he understands the frustrations that some parents may feel, especially if they see medical marijuana as an effective alternate remedy. But, still, he cautioned against universal adoption of the drug too early.

“While I’ve seen a lot of impressive outcomes with medical marijuana, it’s not as good as everyone says it is,” Zempsky said. “We have to be careful of letting things get out too far ahead of us, because we don’t know long-term risks, especially for child patients.”

He’s not outright opposed to prescribing the drug for children suffering from certain conditions, like epilepsy. He simply argues that there isn’t enough data out there to know how adolescent use of medical marijuana affects patients later in life.

“If you give medical marijuana to someone who’s 13, you need to know what they’re like when (they’re) 40,” he said. “That takes time, and there’s no way to expedite that. So we won’t be comfortable for years in the pediatric world to open the floodgates, even if we’re comfortable in the adult world.”

But research is needed. And Rep. Gail Lavielle understands that.

The Republican from Wilton became a vocal supporter last spring for medical marijuana in the state — both as an elected official and a mother.

“When you’re a parent, you want to do everything you can to help your child. You’re not going to put your child in danger voluntarily,” she said. “So you must be pretty desperate to try and find something to help them if you’re willing to consider something that you’re not totally sure of the risks of.

“So I listened to this, and I decided it wasn’t up to me to decide, that it would be supreme and egregious arrogance to think otherwise,” she added.

Lavielle stresses that she’s not “pro marijuana,” especially when it comes to recreational use. But in conversations with her constituents who have epileptic children, she realized the government shouldn’t create unneeded roadblocks.

“My stance is that it’s not up to me as a legislator, as a member of the government, or to the legislature itself to tell people whether they can try something that they think might work when their child has a very grave disease,” she said.

Her colleagues agreed: The bill passed 129-13 in the House and 23-11 in the Senate in May 2016.

Doing everything possible

Meanwhile, away from the Capitol and long-winded debates over policy, children like West Tarricone live the reality of that decision, their families hoping for continued success with treatment.

The 9-year-old from Windham doesn’t let anything slow her down. Her personality is bright and bubbly. She’s affectionate, grabbing the hands of new acquaintances as she leads them around her living room.

Tarricone says her daughter loves to laugh, especially at the pratfalls and tumbles her twin brother makes while they play.

The levity helps, Tarricone said. It takes the family’s collective attention away from the epilepsy. So does the cannabis oil.

What started as a seeming long shot, an idea that Tarricone first had three years ago, now sits in the family’s medicine cabinet, ready to soothe the seizures when they overtake her daughter.

“If you were in our position and you were running out of all pharmaceutical options, and here’s this hope at the end of a really bad tunnel for a child who’s going to prematurely die, you’re going to know,” Cara Tarricone said.

“Because when you look in your child’s eyes, you know you have to do everything possible to help them.

Via Associated Press Member Exchange. Information from: Hartford Courant