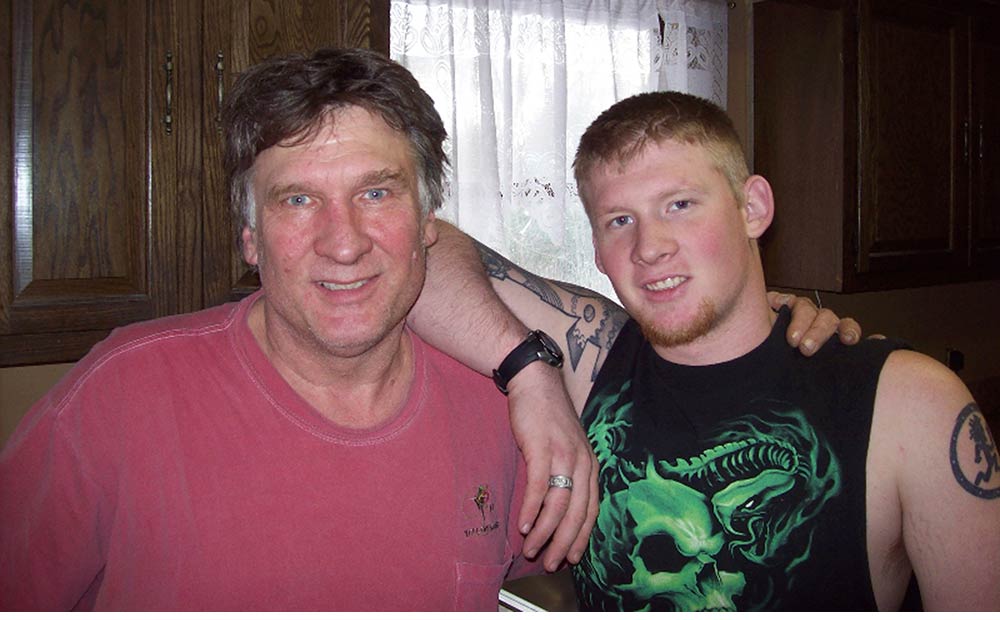

NEW YORK — He slept next to his son’s ashes most nights back when Kraig Moss first met Donald Trump.

In a hall packed with Iowa voters, the presidential candidate looked the middle-aged truck driver in the eye and vowed to fight the opioid crisis that killed his only son two years earlier.

“He promised me, in honor of my son, that he was going to combat the ongoing heroin epidemic,” Moss said of the January 2016 interaction. “He got me hook, line and sinker.”

Moss, an amateur musician, quickly sold enough possessions to fund a months-long tour of more than 40 Trump rallies, where he serenaded voters with pro-Trump songs. His guitar, and the ashes of his late 24-year-old son, Rob, were always close by.

“I had everything riding on the fact that he was going to make things better,” Moss said. “He lied to me.”

Trump’s budget proposal, released this week, would reduce funding for addiction treatment, research and prevention. The most damaging proposed cut, critics say, is the president’s 10-year plan to shrink spending for Medicaid, which provides coverage to an estimated three in 10 adults with opioid addiction. Members of Congress have said they are unlikely to approve the budget as written.

The blueprint comes weeks after the president celebrated House passage of a Republican health care bill that would dramatically reduce Medicaid coverage, while allowing states to weaken a requirement that private insurance cover addiction treatment. A Congressional Budget Office report on Wednesday said a patient’s cost of substance abuse services could increase by thousands of dollars a year in states that chose to weaken coverage requirements.

Some see the moves as a painful betrayal of Americans whose families have been devastated by addiction and trusted the president’s repeated pledges to make them a priority once in office. Trump’s budget priorities focus on tax cuts, military spending and border security with massive cuts to programs for the poor and disabled.

Those most frustrated include parents who shared their stories with Trump.

“We want to help those who have become so badly addicted,” Trump insisted during a late-March “listening session” on opioid and drug abuse at the White House.

Attendees included Pam Garozzo, of Morrisville, Pennsylvania, whose 23-year-old son died of an overdose in December. Trump’s budget requests, Garozzo said this week, run “counter to what we thought he was going to do.”

“That would be a tragedy,” she said. “We’re losing a whole generation of young people to this disease.”

Others responded with similar frustration.

“I didn’t see this coming,” said Paul Kusiak, of Beverly, Massachusetts, who shared with Trump the story of his two sons’ successful battle with opioid addiction during a New Hampshire roundtable discussion eight days before the election. “I’m trying desperately to have hope and take the president at his word.”

During the roundtable, Trump opened up about his father’s struggle with alcoholism. It was enough to convince skeptics in the room he was serious about an epidemic the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says kills 91 Americans each day.

“I believed that he had learned something new and was going to do something about it,” said Patty McCarthy Metcalf, who leads the advocacy group Faces and Voices of Recovery. “He’s let us down.”

Trump has tapped New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie to lead a task force to combat the opioid crisis. Trump’s budget request, however, raises questions about whether he’s committed to new programs.

In some cases, the budget would maintain funding levels, such as $1.85 billion for block grants to states that provide addiction treatment for 2.5 million Americans. Funding has been flat for a decade, and advocates say the grants have lost more than $480 million in purchasing power over that time because of inflation.

Trump also would cut funding for addiction research and eliminate support for the training of addiction professionals. He wants to cut prevention programs by more than 30 percent, according to one advocacy group’s analysis. Trump would cut millions of dollars of federal support of drug courts, prescription drug monitoring programs and state programs aimed at prescription drug overdoses.

The White House did not respond to a request for comment about the president’s commitment to the nation’s opioid epidemic, which has ravaged many of the rural areas and small working-class towns where the Republican drew a lot of support.

Trump’s budget turned back from an earlier plan to gut the office of the White House “drug czar.” In a statement Tuesday, Richard Baum, acting director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, said the budget “demonstrates the Trump Administration’s commitment to stopping drugs from entering the country and supporting treatment efforts to address the burgeoning opioid epidemic.”

Trump voter Michelle Jaskulski, of Milwaukee, who has a son and stepson in recovery from opioid addiction, believes in the president’s commitment and overall approach. “Money for treatment isn’t necessarily a cure-all,” she said.

Many others touched by the opioid crisis say they’re angry and afraid.

“Inside I’m screaming,” said Sandra Chavez of Sacramento, California, who lost her 24-year-old son, Jeffrey, to a blood infection related to his injection drug use. “We’re going backward with Donald Trump’s plan.”

In Cleveland, a state that gave Trump a critical victory, 36-year-old Justin Butler worries he’ll be back on the streets using and selling heroin if Medicaid no longer paid for his treatment. Butler began his recovery in July after being revived from an overdose in a restaurant parking lot. Trump, he said, is “turning his back on people. He’s a liar.”

The sense of betrayal is perhaps deeper for Moss, 58, who devoted much of last year to promoting Trump’s candidacy.

He’s back to driving trucks from his home in Owego, New York. He says that perhaps he shares some blame for investing too many emotions into Trump’s promise.

“Maybe I felt by combatting the heroin epidemic that was going to make me feel complete, as far as losing my son and being able to move on,” Moss said. “And maybe that’s why it feels like such a letdown he’s not fulfilling his promises.”

Johnson reported from Chicago. AP writers Mark Gillespie in Cleveland and Michael Catalini in Newark, New Jersey contributed to this report.