Even before his suicide at age 67, celebrating Hunter S. Thompson’s larger-than-life personality was an obsession for many of his fans.

As one of Colorado’s most famous writers, the gonzo journalist and author of “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” built a mythic persona for himself on his 42-acre Owl Farm in Woody Creek, where half of Thompson’s remains were ceremoniously blasted from a 150-foot-tall cannon after his cremation in 2005.

Related: Check out this slideshow of Thompson-related photos

But a flurry of activity surrounding Thompson’s estate — including a new film being produced in Colorado this summer, plans to open Owl Farm to the public, a potential touring museum exhibit and Thompson’s prescient political writings — is re-igniting the debate over whether the writer’s famously drug-fueled lifestyle overshadows his influential work.

“This is going to be a big year,” said Thompson’s widow, Anita, the founder of the nonprofit Gonzo Foundation who has lived at Owl Farm for the past 17 years. “I decided not long after he passed away to make it a museum, but in my mind it was going to be a lot faster. I’ve gotten so many letters and e-mails from his readers, and in the very beginning there was so much focused on his lifestyle that it made me uncomfortable and a little worried about his legacy.”

More on Hunter S. Thompson

Strain in his name: Want to smoke Hunter S. Thompson’s weed? Gonzo brand marijuana in works

Museum: A Hunter S. Thompson museum is planned for his Owl Farm near Aspen

Blissed Out on Owl Farm: At NORML’s party on Hunter S. Thompson’s land

Weed news and interviews: Get podcasts of The Cannabist Show.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Watch The Cannabist Show.

“People just know him for the drugs, basically,” said Josiah Hesse, a Denver writer who was invited by Anita Thompson to be a writer-in-residence at Owl Farm in November. (Full disclosure: Hesse has contributed to The Denver Post and its marijuana website, The Cannabist.)

“They don’t always acknowledge how prolific he was and how hard he worked, or how sensitive he could be as a sort of softhearted Southern gentleman at times,” Hesse said. “When that is talked about, it’s usually dismissed because of these unsavory aspects of his character.”

Those elements included an unstable and warrior-like personality, heavy drug use, obsession with guns and violence and, finally, inability to control his bowels after decades of alcohol abuse, according to Thompson’s son, Juan, in his memoir, “Stories I Tell Myself,” which was published in 2016. (The Post’s attempts to reach Juan for this article were unsuccessful.)

“After he was dead, I really believe that he would have wanted me to be as honest as possible without causing harm to other people,” Juan said in an interview with Esquire magazine last year. “Tell the whole story.”

Art and artist

Separating art from the artist is often difficult. In Thompson’s case, it is nearly impossible.

As a journalist and activist, Thompson had a habit of making himself the main character in the events he covered, including “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” the career-defining book published in 1971 that found Thompson “successfully straddling the line between journalism and fiction writing,” according to The Paris Review.

At one point in “Fear and Loathing,” Thompson attends the National District Attorneys Association’s Conference on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs for Rolling Stone magazine — an event at which Thompson, “in the grip of a potentially terminal drug episode” and ostensibly on the lam, is surrounded by stone-faced cops. The passage is one of Thompson’s best, peppered with his blend of dark humor, paranoia and social commentary.

“I flew out to Las Vegas with him for that from Aspen,” said Gary Wall, 75, a former Aspen police officer and, later, Vail police chief, who befriended Thompson during the writer’s run for Pitkin County sheriff in 1970 (immortalized in the Rolling Stone article “The Battle of Aspen”). “I was the angry guy checking into the room in front of him in line (in the book), and I went out drinking with him, Oscar Acosta (Thompson’s attorney, a.k.a. Dr. Gonzo) and deputy DA Jimmy Moore that night.”

Wall’s recollections of the conference, as well as other events he witnessed with Thompson through the years, differ significantly from Thompson’s accounts. But that doesn’t surprise Wall, “the first cop Hunter ever called,” given the partly fictionalized nature of Thompson’s writing.

“He gave me a copy of ‘Fear and Loathing’ and wrote in red ink on a couple of pages, which my son wants when I croak,” Wall said. “Next time I saw him in Aspen, I said, ‘I read your book. That’s not the same kind of things I remember!’ And he said, ‘Yeah, but you weren’t on the same trip I was on.’ ”

Thompson has been lauded and criticized for using his persona to manipulate people for his own competitive purposes. But the cult of personality he created never got in the way of his decency, said Wall, who now lives in Steamboat Springs.

“He’s perceived to be this crazy, drug-addict nutcase, and that’s not true,” said Wall, who shared Thompson’s libertarian philosophies. “I always had wonderful conversations with him, which doesn’t mean he wasn’t on drugs, but I recall him something totally different than what he is perceived to be. He never talked the way he writes — which is kind of how Donald Trump talks, saying any (freaking) thing he feels like saying. And if he had won his campaign for sheriff, I would have happily worked for him.”

Not always positive

Regardless of Thompson’s intentions, the impacts of his unpredictable personality were not always positive, especially on young women, “whom he was known to exhaust, abuse and addict,” said Denver writer Laura Bond, citing E. Jean Carroll’s book “The Strange and Savage Life of Hunter S. Thompson” and other published accounts.

“I think it’s preferable and possible to be a good person and a good artist. I’m also of the opinion that (Thompson) was neither, particularly. … His destructive tendencies were so romanticized, and he did a lot to perpetuate the idea that creativity and freedom are fueled by drugs and alcohol. That idea has taken a lot of people down dangerous roads,” Bond wrote via e-mail.

“It’s probably not (his) fault that he inspired a generation of imitators, but as a former music editor (at Westword), I do hold it against him, having faced more than my fair share of incoherent first drafts from wannabe gonzo journalists,” she wrote. “That idea, along with his misogyny, just feels totally outmoded, uninteresting and sad to me today.”

Thompson claimed he was the subject of a “witch hunt” in 1990 after Gail Palmer-Slater of Port Huron, Mich., accused Thompson of grabbing her breast and throwing a drink at her at Owl Farm, according to The New York Times. After being cleared of charges for drug possession, explosives possession and sexual assault, the the-53-year-old Thompson called for a “celebratory orgy” at Woody Creek Tavern, a favorite hangout of his in the Roaring Fork Valley.

“Personally and professionally, Hunter worked best with women publishers, assistants and editors,” Anita Thompson wrote via e-mail, in response to Bond’s comments. “Hunter’s loyalty to friends and colleagues, especially women, and his generosity of spirit live on through his work and those who actually knew him.”

Regardless of their opinion of him, fans and critics have acknowledged that Thompson’s work deserves serious historical analysis, especially in the way that he chronicled different aspects of the American Dream — or rather, for many, its disintegration.

On Dec. 15, The Nation published an essay titled “One Political Theorist Predicted the Rise of Donald Trump. His Name Was Hunter S. Thompson.” In it, writer Susan McWilliams references Thompson’s 1966 “Hell’s Angels” book (which began as an essay for The Nation) and the outsider anger of “left-behind” Americans that Thompson seemed to understand so well, and which motivated their “ethic of total retaliation.”

“In certain turns of phrase, he could capture the spirit of America, not only at that time but decades after,” said Carolyn Bielfeldt, a former editor at Vanity Fair who worked with Thompson on his final book, 2005’s “Hey Rube: Blood Sport, the Bush Doctrine, and the Downward Spiral of Dumbness.” “His view of American and world politics was so on point and profound and now, eerily prophetic. Even to the last days of his life, even if his mind wasn’t always there, he was devouring the news, reading every newspaper and being an oracle who foresaw what was coming.”

Thompson’s third-party run for sheriff offers many parallels for today’s political climate, said Bobby Kennedy III, a part-time Aspen resident who is using a $300,000 rebate from Colorado’s film office to begin shooting his historically based movie, “Freak Power,” in Colorado in June.

“I just really want to motivate a bunch of young 20- and 30-year-olds to get back into politics right now,” Kennedy, the grandson of Robert F. Kennedy and the son of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., told The Post in December. “A lot of people really put their hearts into this election, and I don’t want to have this movement that sort of started here in Colorado … we’re right on the verge of losing it, and I want to bring it back on the big screen.”

Thompson’s legacy

The “Freak Power” movie has the potential to add to Thompson’s charismatic, combative legacy with a film depiction that can’t help but build on Johnny Depp’s (from 1998’s “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas”) but also Bill Murray’s (in 1980’s “Where the Buffalo Roam”). But the “Hollywood-ization” of Thompson will always be a side issue, said Daniel Joseph Watkins, an Aspen curator who wrote the 2015 book “Freak Power,” from which Kennedy is drawing some of his script inspiration.

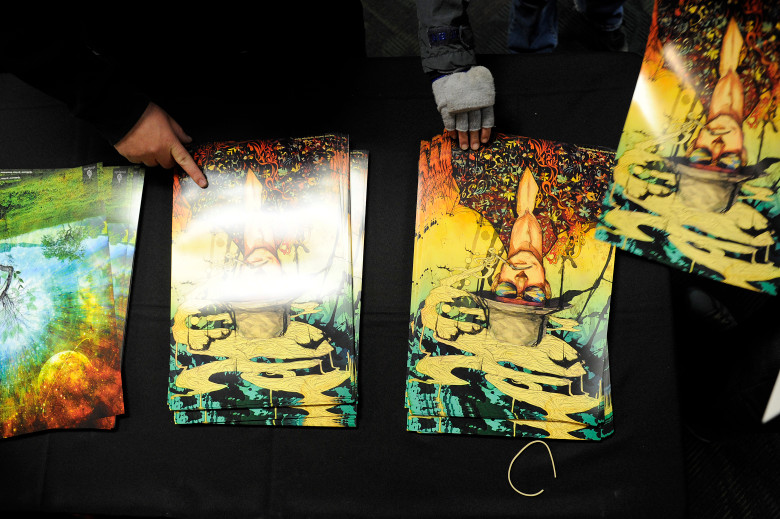

“Part of what I was trying to do was bring the conversation back to the fact that he was a really serious writer and had these powerful ideas,” said Watkins, who operates the Thompson-centric Gonzo Gallery — including artwork from Thompson collaborators Thomas W. Benton and Ralph Steadman — in different locations around Aspen.

Watkins said he is in talks with several museums and journalism schools about bringing a 125-piece collection of Thompson memorabilia (including original “Freak Power”-era posters, photos and articles) on a national tour in 2020 to coincide with the next presidential election, as well as the “Freak Power” campaign’s 50th anniversary.

“I want to make a lasting contribution to the understanding of his political work, but Anita (Thompson’s widow) is already doing a fantastic job of keeping his legacy alive in so many different ways,” Watkins said.

Of course, one of those ways includes marketing a marijuana strain under the Gonzo brand, as Thompson’s widow has announced plans to do, as well as opening her home to the public later this year. It will be modeled in part after the Key West, Fla., home-museum of Thompson’s idol Ernest Hemingway (from which Thompson once famously stole a set of antlers and which Anita returned last year).

“His works are taught in more colleges and high schools than when he was alive,” Anita Thompson said. “That’s exactly what I was hoping for. Now we can celebrate all of his life, (including) his sense of fun and love of the wilderness. His lifestyle was a tool, not an obsession of his.”

Anita Thompson does not deny that her husband had problems, saying there is “no doubt” that he was an alcoholic. But since taking ownership of Owl Farm last summer, as well as the rights to Thompson’s likeness and name, she is confident that Thompson’s legacy is firmly centered on his writing, not his lifestyle.

“I only ever saw him drunk twice,” she said. “He didn’t like having drunk people around, and if he believed the drugs were interfering with his work, then it was time to stop and start over the next day.”

But the questions hang: Does having a posthumous, branded cannabis strain undermine the esteem of being a visionary political and social commentator? Do Thompson’s addictions and instability outweigh the wide-ranging impact of his writing and activism after his death?

As with his best-known work, there are no objective answers, only lasting results, said former Rocky Mountain News reporter Jeff Kass, who met Thompson in the late 1990s and eventually befriended him.

“When I say I covered Hunter for the last five to six years of his life, I wasn’t writing about him being a crazy, drug-addled personality,” said Kass, now a Denver-based private investigator. “I was writing about him taking on a public legal crusade to get a convicted felony murderer (Lisl Auman) out of prison. And you know what? Two days after they blasted his ashes out of a cannon with a hundred people under it, it worked. What’s crazier than believing that you can get a felony-murder conviction overturned? And then actually doing it?”