For eight years, Rajuawn Middleton, an assistant at a major downtown law firm, lived in a four-bedroom, red-brick home she rented on a quiet, tree-lined street in Northeast Washington — until she was forced out over a few cigarettes containing a “green leafy substance.”

In March 2014 police arrested her adult son on charges of possessing a handgun outside a nightclub. He had not lived with Middleton for years, but two weeks later D.C. police looking for more guns raided her home.

The routine search placed Middleton in the grip of an indiscriminate bureaucratic mechanism known as nuisance abatement, a mild-sounding term for a process that has had harsh and disproportionate consequences for Middleton and other District residents.

Middleton said a dozen officers stormed in as she and her husband were helping their 8-year-old son with his homework. Police handcuffed the couple, cut open a mattress and dumped food on the floor, she said. The search turned up three cigarettes; Middleton said only one of them was a joint of marijuana. No firearms were found. No one was charged.

Related marijuana news: Know your rights

In California: Can California landlords evict their tenants for smoking legal weed?

Ask The Cannabist: Pulled over by police? Know your rights

Pot and the law: Visit our resource page on all things marijuana and the law

Weed news and interviews: Get podcasts of The Cannabist Show.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Watch The Cannabist Show.

Peruse our Cannabist-themed merchandise (T’s, hats, hoodies) at Cannabist Shop.

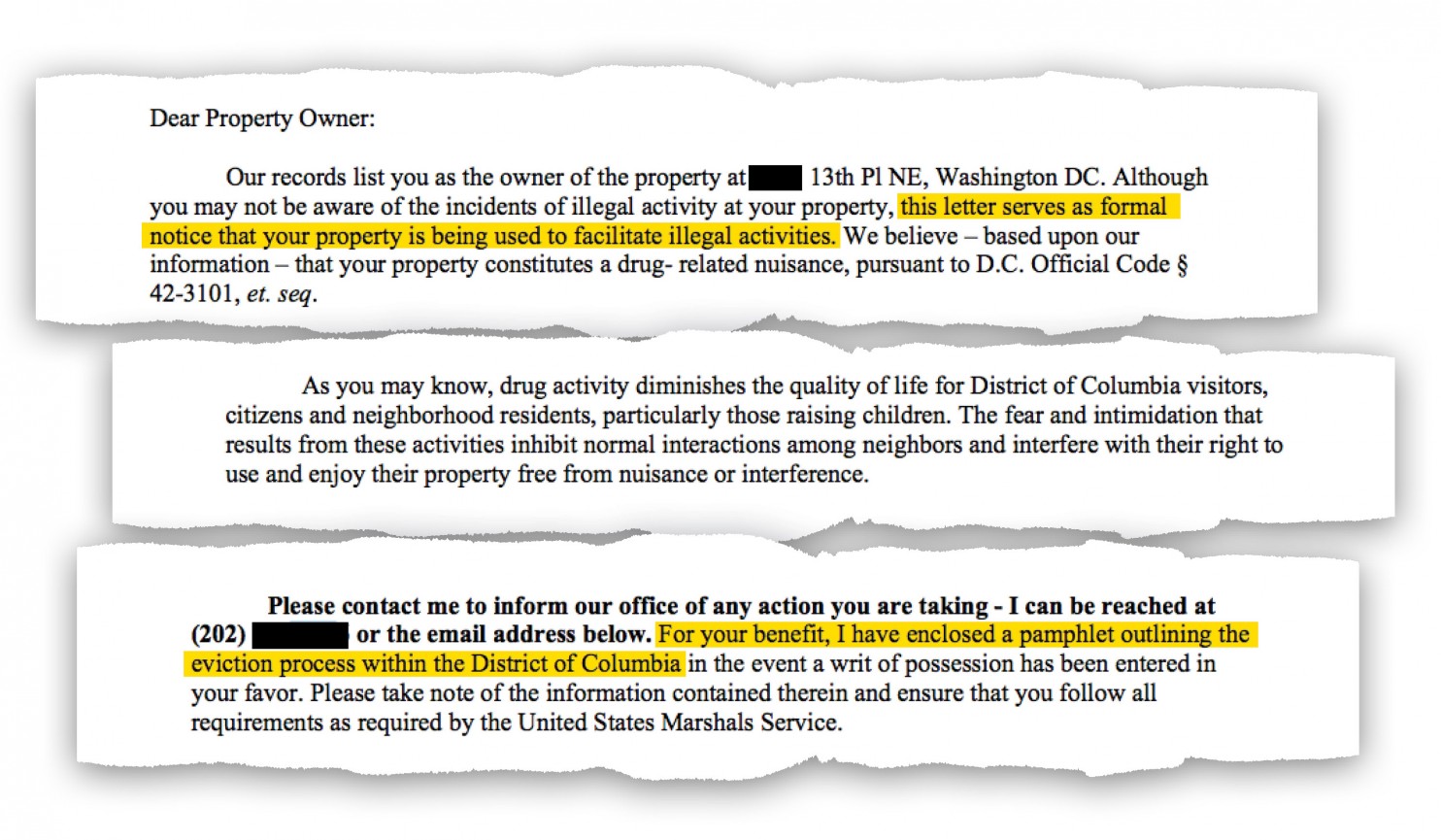

A week later, the D.C. attorney general’s office deemed the house a “drug-related nuisance” in a form letter sent to Middleton’s landlord. “The fear and intimidation that results from these activities inhibit normal interactions among neighbors and interfere with their right to use and enjoy their property,” said the letter signed by Assistant Attorney General Rashee Raj Kumar.

The letter cited a 1999 law that gives broad power to city officials to sue property owners who fail to stop illegal activity at their properties.

The landlord moved to evict. Middleton moved out.

During the past three years, city officials sent out about 450 nuisance-abatement letters to landlords and property owners, the vast majority aimed at ousting tenants accused of felony gun or drug crimes, including many bona fide drug dealers. But in doing so the District has also ensnared about three dozen people who were charged with misdemeanor marijuana possession or faced no charges at all, a Washington Post review of the letters has found.

The attorney general’s office in January sent a nuisance letter to one property over one gram of marijuana, a legal amount of the drug in the District. As a result, the property company forced a grandmother out of her Southwest Washington apartment, records show.

The Post found that some cases were driven by an assembly line of government agencies that merely processed paperwork and failed to differentiate between dangerous felons and people such as Middleton and the grandmother in Southwest.

The process is typically set in motion after D.C. police raid a residence and then send information about what they find to the U.S. attorney’s office, the federal agency charged with prosecuting crimes in the District. The police refused to discuss the cases reviewed by The Post or explain how they decide which properties to flag.

The U.S. attorney’s office said they only pass referrals from police to the D.C. attorney general’s office, the legal arm of the District government.

The attorney general’s office is supposed to review the cases and determine whether a property constitutes a nuisance.

Officials with the attorney general’s office now acknowledge that their office failed to do that adequately. During the reporting of this story they did not point to a single instance over a three-year period where they had not issued a nuisance letter in response to 450 referrals from police. After the story appeared online, they identified seven cases over the past year where the nuisance was resolved without the need for a letter.

When presented with The Post’s review of all their nuisance-abatement letters sent since mid-2013, the office issued a moratorium on them, pending a review.

“We can’t just be the rubber stamp for what some other agency is doing,” said Deputy Attorney General for Public Safety Tamar Meekins. “We have to engage in our own independent professional judgment about these things.”

The D.C. Council passed the Drug-, Firearm-, or Prostitution-Related Nuisance Abatement Act in the late 1990s, when officials were grappling with the aftermath of the crack-cocaine epidemic. For years, drug dealers had used neglected properties across the city to store and sell narcotics and weapons, making them havens for drugs, violent crime or prostitution.

Modeling the law after zero-tolerance policing policies in New York, council members gave city attorneys and community groups power to sue landlords who failed to combat illegal activity at their properties.

The broadly worded law can cover any property where police have served a search warrant for drugs, weapons or prostitution, or that has prompted repeated complaints from neighbors.

Police search thousands of properties each year, identifying between 100 and 200 per year as potential nuisances, records show. Police did not provide The Post with any written guidelines or policy for how they flag properties as nuisances. A police spokesman said supervisors select the ones where people “have engaged in drug trafficking, the sale of weapons, or prostitution.”

Police send those cases to the U.S. attorney’s office for the District, where a paralegal forwards them to the D.C. Office of the Attorney General, said a U.S. attorney’s spokesman.

At the attorney general’s office, a unit of five lawyers in the Neighborhood and Victim Services Section is supposed to examine each case to determine whether the property fits under the nuisance law.

Landlords who receive letters have two weeks to eliminate the nuisance or the city can sue to seek damages or seize the property. The nuisance letter does not require an eviction, but roughly half the letters reviewed by The Post included a pamphlet outlining the eviction process.

Landlords, tenants and advocates said the attorney general’s office almost always urged landlords to pursue that course.

“Unfortunately, that means a lot of tenants are dragged into court who shouldn’t be, and a lot of landlords are being forced to bring these [eviction] cases even when they don’t have enough evidence,” said Beth Harrison of the Legal Aid Society of the District of Columbia.

Rob Marus, a spokesman for the attorney general, said that most of the cases reviewed by The Post occurred before Karl Racine became the first elected attorney general in the District and took office in January 2015.

Marus acknowledged that the letters used by the office failed to inform landlords of steps they could take short of eviction. He said the office is now revising the language of its letters to encourage landlords to consider other options.

In the majority of cases reviewed by The Post, city officials targeted serious offenders.

In one case from 2013, police raided an apartment in Washington’s Dupont Park neighborhood and uncovered 548 grams of crack, 22 grams of heroin and five guns. The attorney general deemed the property a drug and firearm nuisance and told the landlord to take action. The landlord sued the tenants, and they moved out.

Last year, the attorney general’s office used the law to shut down an electronics store in Bloomingdale where police seized more than 800 packets of synthetic marijuana. And, in one of the biggest cases to date, the District in January won a $3.3 million judgment in a nuisance action against a landlord who allowed tenants to operate brothels in Dupont Circle.

But D.C. Council member Jack Evans (D-Ward 2), who sponsored the nuisance law in 1998, said people such as Middleton were not whom the city had in mind when the council approved the ordinance.

“Is someone who has a joint in a house the nuisance we’re looking for?” Evans said. “The immediate answer would be no.”

Jasmine White, an advisory neighborhood commissioner for the District’s 5th Ward, got caught up in the nuisance law after she rented a room in her Fort Totten apartment to a cabbie. For two years the arrangement worked well. Her roommate wasn’t home much, and White said she used the solitude to study for her master’s degree at the University of the District of Columbia.

In March 2014, U.S. Park Police caught the roommate speeding in Fort Dupont Park. During the stop, officers smelled marijuana and asked to search, records show. They found eight ounces of the drug inside his car. Police arrested him on a charge of possession with intent to distribute. He later pleaded guilty to a lesser charge.

The next day, police showed up at White’s apartment and asked if they could search the roommate’s bedroom. He was not home, and White hesitated. She did not have access to his room, she told them. She said she would feel more comfortable if they returned with a search warrant.

“That is when they became hostile and started to threaten me about what they would do with my apartment, what they would do to me for not letting them in,” White said. “I was really scared.”

The following day, more than 10 officers, guns drawn, returned to her apartment, this time with a search warrant, she said. Police handcuffed White and sat her in the hallway as neighbors watched. In the roommate’s room, they found a small amount of marijuana, paraphernalia, shotgun shells and $1,361 in cash, records show.

White, who was not arrested or charged with a crime, explained what had happened to the manager of the complex.

“I told him this has nothing to do with me,” White said. “He told me not to worry about it because I could make my roommate leave.” The manager confirmed the account to The Post.

That was before the matter landed on the desk of Kumar, the assistant attorney general, who sent a letter to White’s landlord deeming White’s apartment a drug nuisance. In addition to noting the marijuana, the letter claimed police had found a shotgun, though search records show they found only several spent shells.

An attorney who represents Borger Management — the property manager for White’s building — and other landlords told The Post that landlords frequently file for eviction after receiving nuisance letters because they do not want to risk their property in litigation with the city.

Weeks later, White found an eviction notice naming her taped to her door. She felt that she had little choice but to settle the case and move out. White said she feared that a drug-related eviction would preclude a political career.

The roommate received a three-month suspended sentence on the drug charge.

White said she feels like the ordeal has tarnished her reputation.

“As an elected official I had aspirations of possibly pursuing other public office,” White said. “But now I just don’t think that that’s a possibility.”

Charge dropped, still targeted

Larry Tutt said he was nearly put out of his apartment in August 2013 after police raided his home because they smelled marijuana outside his door.

The 61-year-old is well known to locals near the Farragut North Metro station. He often spends his mornings there greeting commuters with a bright smile, his signature singsong call of “good morning,” and a cup for spare change. Until recently, he rented an apartment through a medical-treatment program in Washington’s Trinidad neighborhood, a rapidly gentrifying area police monitor closely for drug activity and violent crime.

Tutt, who has schizophrenia and walks with a cane, said he had just gone to bed one night when police knocked on his door. The vice squad officers said they were doing an investigation nearby and smelled marijuana coming from his apartment. They asked to search it, Tutt said.

As a younger man, Tutt had many run-ins with the law, including a burglary conviction in the mid-1990s that landed him in prison for 10 years. He told the officers that he smoked marijuana to medicate his mental illness but said if they wanted to search, they should come back with a warrant.

The next night, they did. Nine officers broke down his door with a battering ram, handcuffed him, flipped over a recliner — one of his only pieces of furniture — and dumped drawers of clothes on the floor, he said. They found a grinder with marijuana residue and arrested him on a charge of misdemeanor possession. He spent the night in jail. Three months later, prosecutors dropped the charge.

That same week, however, Assistant Attorney General Argatonia Weatherington sent Tutt’s landlord a nuisance letter, saying “drug and/or gun activity” at Tutt’s apartment was harming the neighborhood.

“It is your responsibility to ensure that your property is not used in a manner that is detrimental to the welfare of the surrounding area,” the letter said.

Tutt said his landlord called about the raid.

“He said, ‘You’re selling big drugs,’ ” Tutt recalled.

Tutt’s caseworkers and family members intervened. They said they asked the landlord and the attorney general’s office not to kick him out, saying he wasn’t involved in drug dealing.

After talking with Tutt and his sister, lawyers in the attorney general’s office realized that Tutt was not a drug dealer and they should not have targeted his apartment for eviction, the office said.

Tutt kept his apartment. The landlord declined to comment on the case.

Tutt said he eventually moved out because of the raid. He said he has had recurring nightmares about police breaking down his door. He now lives in a different neighborhood, where he said he is sleeping better.

‘You can fight’

Housing advocates and landlords said the nuisance letters can give property owners more leverage to evict tenants they see as problematic.

In March 2014, Howard University student Jeffrey Gibson and four other students were renting a rowhouse in Northwest Washington. One roommate was about to enter the U.S. Air Force, another a top scholar who managed a local GameStop. Two others studied communications. Gibson was president of a fraternity for students majoring in insurance studies.

Gibson and the other students said they and their landlord disagreed over who was responsible for the condition of the home, including holes in the walls and cracked floorboards. The landlord, Eugene Banks, said through his attorney that the students threw parties and refused to clean up after themselves. Banks wanted them out, but they still had months to go on their leases, his attorney told The Post.

Neighbors complained about the students. Police had visited the house dozens of times between fall 2013 early 2014, according to records and interviews.

“We weren’t throwing parties,” Gibson said. “We were working jobs after school and may not get home until 12 a.m. Then we’re up doing homework until 4 a.m. Our schedules were opposite.”

Officers would tell the students to keep quiet, then move on, roommates said.

But one evening in February 2014, police arrived at the home with a warrant to search for drugs. In an affidavit, police told a judge they had smelled marijuana coming from the house during a recent visit to investigate a complaint.

Gibson said he was in his bedroom watching a basketball game when police kicked down his door and pointed shotguns at him. Officers handcuffed the students and searched the rooms, dumping out cereal boxes and emptying drawers. They found a small amount of marijuana, a tobacco grinder and an Adderall pill that belonged to a roommate who said he had a prescription, according to records and interviews.

Police arrested two roommates and kept them in jail over the weekend. They were not charged.

A month after the search, Weatherington, the assistant attorney general, sent a letter to Banks calling the house a “drug and/or firearm related nuisance.”

Banks sued to evict all five students.

At first, Gibson and his roommates contested the suit. They weren’t drug dealers, they all had clean records and they needed a roof over their heads until they graduated, Gibson said.

Banks’s attorney, Thomas Hart, blamed the students for damage to the house and said they violated their lease by having guests for extended stays.

“They massacred the house,” Hart said. “This was not the case where out of the blue he just turned on them and kicked them out. It was a string of problems.”

Useful weed resources

Strain reviews: Check out our marijuana reviews organized by type — sativas and sativa-dominant hybrids, ditto with indicas.

Favorite strains: 25 ranked reviews from our marijuana critics

Follow The Cannabist on Twitter and Facebook

Shortly after Banks sued, two roommates agreed to leave. After months of legal proceedings, Gibson and the others agreed to leave at the end of the summer.

Gibson said he and the other students didn’t want to be falsely labeled in the eviction as drug dealers.

“You don’t just have to take what they give you,” Gibson said. “You can fight.”

Forced out by form letter

When Middleton first moved into her home on 13th Place Northeast, she said she felt like she had won the lottery. Securing a home through the city’s Section 8 housing program had been a long shot. Many of her friends, she said, waited years.

Over the several years that she lived there, she said she worked hard to protect the house where she was raising her four children. In 2011, she said she kicked out one of her sons after he was convicted of unlawful possession of a firearm. She said she was worried she could lose her voucher.

“There’s two people I don’t mess with — housing and the tax man,” Middleton said.

When police arrested the same son outside the nightclub in March 2014, he was living in Fort Totten, she said. Police said they had found him in a car with a handgun in the glove compartment and located her address on his ID and in criminal court records. He was eventually found not guilty of gun charges.

The police raid at her home turned up hand-rolled cigarettes containing “a green leafy substance,” according to police documents.

Middleton called her landlord and assured her that no one in the house sold drugs. But the landlord told her she had to leave.

“She said, ‘I have to believe this because it’s coming from the attorney general,’ ” Middleton recalled.

The landlord’s attorney, Bernard Gray, said he empathized with Middleton but was obligated to proceed with an eviction.

“I take action because if I don’t, my client is in jeopardy,” Gray said.

Initially, Middleton refused to leave. She said the landlord stopped maintaining the house and she stopped paying rent.

After several months, Middleton moved to another part of the neighborhood. Her new house is smaller, and she said she fears for her family’s safety. Her young son has been awakened by the sound of gunshots, she said.

“The whole process was haywire,” Middleton said.

This report was produced in partnership with the Investigative Reporting Workshop at American University, where Hawkins and McCormick were students.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this story, based on interviews with lawyers at the attorney general’s office, said the office had not rejected any of the 450 cases referrals it received for nuisance letters over a three-year period. After the story was published, an office spokesman said seven cases were resolved without letters in the past year.