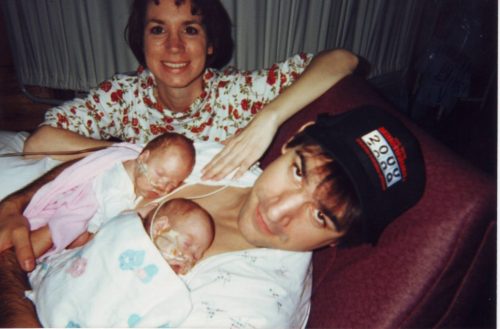

Kara Zartler’s life began too soon.

Along with her twin sister, she was born 26 weeks early. At 1 pound 12 ounces, she weighed slightly less than the healthy Keeley. Then, 10 hours into life, Kara suffered a brain hemorrhage. Seventeen years later, she’s lucky to be alive. But she has cerebral palsy and severe autism, which in her case causes compulsive self-injurious behavior that began with she was four years old.

“It’s a terrible sight to see,” her father Mark Zartler told The Washington Post via telephone from his home in Richardson, Texas. “She hits herself in the face repeatedly. She gets into a loop, and she can’t really stop. Sometimes she can self-recover, but other times it just extends and extends and extends.”

After years of trying different drugs with little luck, Zartler eventually gave Kara marijuana on the advice of a friend, even though it’s illegal in his home state of Texas. To his surprise, it worked. Now, years later, he’s chosen to go public with his story – though he risks potentially unwanted attention – in hopes of changing his state’s laws. Currently, Senate Bill 269 is in committee. If the bill becomes law, as Mark hopes it will, Texas will be the 29th state to legalize medical marijuana, which could change Kara’s life.

PHOTOS: Texas father who treated autistic daughter with marijuana will maintain guardianship

When they began, Kara’s fits, which include hitting, scratching and biting herself, would last for 12 hours. Zartler, a 48-year-old software engineer, and his wife Christy, a pediatric nurse practitioner, would take half-hour shifts physically restraining her, sometimes for an entire day.

“I like to just get her into a bear hug, keep her arms down. She’ll pinch and rip the skin on my hands, but it just doesn’t hurt anymore,” he said.

Her school used a modified straitjacket, but she’d worm her way out of it.

She could inflict severe damage, once breaking her nose. “She’s had cauliflower ears since she was six . . . like MMA fighters,” Zartler said. “She comes home from school with bleeding ears.” Once, she even bit through her mother’s finger, sending her to the hospital.

The family cycled through four neurologists, desperately seeking a solution. Kara was placed on Risperidone, an antipsychotic drug generally used to treat schizophrenia and bi-polar disorder. It was somewhat effective. Slowly Kara had what her parents called “good hours” in which she wouldn’t self-harm, then “good days.” But it didn’t stop the fits, and the medication left Kara slower, foggier. She stopped making eye contact, couldn’t use the restroom on her own.

When she was about 11, a neighbor approached Zartler with an idea: Cannabis.

The drug isn’t legal in Texas, not even in medicinal form save for one small caveat – some people with “intractable epilepsy” might be eligible for low-THC cannabis, according to the Marijuana Policy Project. In all other instances, possession of the drug carries a hefty sentence, often years in prison.

But Zartler felt he was out of options.

“Kara likes the beach, but it’s hard to get there. In the car, at that time, she would last two to three hours before going into these episodes,” Zartler said. “The problem with the car is you can’t restrain her, and she fights back.”

Before one such trip, he fed Kara part of a marijuana brownie his neighbor baked.

“She made it the whole way,” Zartler said. “It was a tremendous success.”

He was new to the drug but learned how to extract the THC into oil and bake such brownies. “Slowly over several years, we introduced it to her life,” he said. Eventually he began using a vaporizer, which like its namesake vaporizes the THC for quick consumption.

Now, Kara is 17. He weaned her off the high doses of Risperidone, and noticed Kara making “huge developmental strides.” She began making eye contact again and can use the bathroom on her own.

“We’re not doing this instead of other options. Kara has had teams of doctors, and it’s always been this way. But there’s no other medicine that relieves her fits once they start,” Zartler said. “There were lingering doubts for years, but I don’t doubt what we’re doing any more.”

Zartler and Christy use the “medicine” less than in the past, but during “high-stress situations,” he’ll still administer it. The day before speaking with The Post, in fact, Kara had a fit. Mark held her in his strong bear hug for an hour, but “finally enough was a enough” and he gave her “a treatment.”

“And she had a great day,” he said. “And she’s not a zombie. She doesn’t just lay there. She just becomes normal Kara.”

When their experiment began, Zartler said, “We thought we were the only people in the world who were crazy enough to do this. We just weren’t connected with any groups . . . I had no earthly idea anyone on earth was doing this.”

But parents across the United States have been attempting to treat autism with marijuana for some time. Though research has found the drug useful in treating epilepsy, only anecdotal links have found it helpful for those with severe autism.

Writer and Fulbright scholar Marie Myung-Ok Lee, for example, wrote in The Washington Post that cannabis cookies calmed her autistic son, who would become “consumed by violent rages” and “bang his head, scream for hours and literally eat his shirts.”

Lee and Zartler are far from the only ones to discover such relief. But they, like many others, face potential criminal charges for administering it. Zartler can’t move – his aging parents and in-laws live nearby and require the Zartler’s assistance. But while he’s in Texas, he’s in jeopardy.

“This is medicine, so we travel with it. If I’m driving through Texas, and I get pulled over,” Zartler said, his Texan drawl trailing off before continuing. “I’m going to be arrested.”

Added Zartler, “At some point in her life, it’s going to be a problem.”

Kara will be in high school until she’s 22. At that point, she might have to go to a group home, which would help socialize her. Zartler worries about getting injured and not being able to care for her. If nothing else, “Kara’s likely to outlive us.”

“It’s one thing for us to break the law, but how much can we ask of her caregivers?” Zartler said. “I can’t ask a third-party caregiver to commit felony.”

“No laws are ever going to change in Texas unless we can say this works,” he said, so he’s sharing Kara’s story with the world.

He knows the risks. “It wouldn’t surprise me if the sheriff knocks on the door of if Child Protective Services knocks on the door tomorrow.” But he feels that they’re worth it.

“Obviously I’m doing an antagonistic thing, but I don’t want to be antagonistic about it,” he said. “We’re hoping with the attention we’re getting, we can influence people into doing the right thing.”

Watch the change as Kara Zartler uses cannabis vapor