Three years after Colorado voted to legalize recreational marijuana, little is known about whether the state’s roads are less safe — and law enforcement efforts remain largely focused on alcohol, not pot.

One glaring example: A Coloradan who pleads guilty to driving under the influence of marijuana is required to install a device on his car’s ignition to measure the alcohol in his breath.

“Basically, I could continue to smoke as much weed as I wanted and the DMV would be none the wiser,” said Colin McCallin, a Denver defense attorney who specializes in DUI laws.

From a lack of statistics to laws that haven’t been updated to disagreements over how to measure whether a person is stoned, there is a lot to be discussed and learned about marijuana and driving.

“There’s a lot of gray area,” McCallin said.

In Colorado, DUI laws don’t distinguish between drivers who are drunk on booze, high on pot or even reeling from oxycodone.

Because Colorado was the first state to legalize recreational marijuana, it has been expected to be a leader in highway enforcement. But there is work to do here and around the country, multiple experts on impaired driving said.

The entire system is based on catching drunken drivers. It has been developed and tweaked for decades by law enforcement, researchers, lawmakers and attorneys.

Colorado police officers spend 24 hours during their basic training academy learning how to detect and test for drunken drivers. And the state keeps extensive data on alcohol-related arrests, collisions and fatalities.

Year in Review: 2015

Local laws: Pot-selling small towns build identity near Colorado cities that ban sales

Unbalanced cannabis landscape: Denver’s pot businesses mostly in low-income, minority neighborhoods

A new calling: Accidental entrepreneurs find skills in high demand as marijuana matures

Normalization: The subtle mainstreaming of cannabis in Colorado is happening everywhere

On the road: A slow shift on working marijuana into alcohol-centered road safety

Kids and cannabis: Marijuana use in Colorado schools still unclear, prevention on the rise

NEW: Get podcasts of The Cannabist Show.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Watch The Cannabist Show.

But the legalization of recreational marijuana in 2014 introduced a whole new set of questions. Among those are how an edible affects driving compared to smoking weed and whether a regular user can smoke more than a novice and still be in more control of a car.

It’s too early to tell how legalization has affected road safety.

The Colorado State Patrol started measuring marijuana-related traffic citations in 2014, said Sgt. Rob Madden, a state patrol spokesman. That year will serve as the baseline for years to come.

“Statistically speaking, you need more than two years of data, and we don’t even have two years yet,” Madden said.

In Washington state — where recreational pot sales have been legal since July 2014 — state patrol officers separate DUI charges into alcohol and drug categories. From there, the office’s crime lab will categorize the drug — whether it be pot, prescription pills or others — based on the request from the officer.

While Colorado law enforcement does test for different drug categories, the charge falls under a general DUI category. Madden said this is because there are many labs in Colorado that do toxicology testing depending on the law enforcement agency, whereas Washington uses a central lab that makes data easier to track and collect.

In marijuana-specific cases, the Washington department can also test whether the THC in the driver’s system was active or whether it had been metabolized.

“But the courts are going to consider everything,” said Sgt. Paul Cagle with Washington State Patrol. “They’re going to look at things like driving and other indicators the officer discovered during the investigation.”

Related

Eyes on the road: Research divided over stoned driving and traffic deaths

A novel way to educate: Why is this Denver attorney giving away rolling papers?

NEW: Get podcasts of The Cannabist Show.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Watch The Cannabist Show.

Because of the way Washington police test for intoxication, the state is able to keep more in-depth statistics on impaired driving.

The state’s report on the involvement of marijuana in fatal crashes between 2010 and 2014 shows an increase in the number of drivers involved in fatal crashes who tested positive for THC. But the report also notes that more information is needed to draw conclusions about the impact of legalized recreational marijuana in the state.

The Colorado legislature has determined that the legal limit for impairment by marijuana is 5 nanograms of THC in the blood. But that limit is a presumption only, unlike the blood-alcohol limit that affirms a driver is drunk if their blood-alcohol concentration is more than .08 percent.

That pot standard already has been rejected by a jury in at least one case involving a medical marijuana patient.

Melanie Brinegar was pulled over in early 2015 for having an expired license plate. The officer smelled marijuana and Brinegar, who works in a dispensary, admitted to using it for medical purposes.

A blood test later found that she had 19 nanograms in her system, a fact she and her attorney, McCallin, did not dispute. Police also asked Brinegar to perform two sets of roadside sobriety tests.

McCallin and Brinegar were able to convince the jury that Brinegar was not impaired because she was a regular user and a better driver after smoking because she was in less pain. She was acquitted of driving under the influence and driving while ability impaired.

“I don’t know if that defense is going to work for a typical recreational case,” McCallin said.

McCallin also criticized the roadside sobriety tests police use to determine if a person is too stoned to drive.

“All of the maneuvers were developed in the 1970s for alcohol impairment,” he said. “We’re seeing law enforcement using those same maneuvers for a completely different drug.”

Police are working to catch up, too.

“Law enforcement is learning right alongside the public in a lot of this,” Madden said.

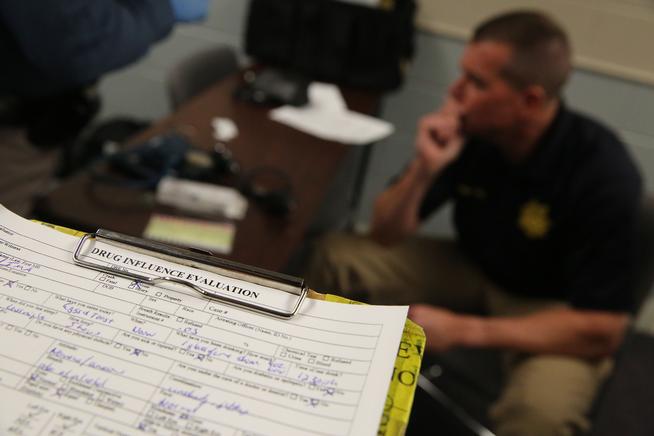

The Colorado State Patrol and the Colorado Department of Transportation are getting more police officers trained as Drug Recognition Experts, a certification which helps them understand how various drugs impact drivers.

Statewide, there are 229 officers certified as Drug Recognition Experts ,and 63 are state troopers, said Glenn Davis, CDOT’s highway safety manager.

Thus far, law enforcement measure marijuana impairment through a blood test.

But a California start-up is developing a hand-held breath test device for marijuana impairment that has piqued the interest of Colorado law enforcement and legislators.

Mike Lynn of Hound Labs, Inc., stands at the intersection of people who want more answers regarding pot and driving.

Lynn also is an Oakland emergency room doctor, a reserve deputy sheriff, and a clinical faculty member at the University of California San Francisco.

Lynn was treating patients involved in marijuana-related traffic collisions and hearing his colleagues at the sheriff’s office voice frustrations over people driving while high.

“I had this perspective where I was seeing it on all fronts,” Lynn said.

His research shows a breath test can accurately detect recent marijuana usage.

“If somebody has it in their breath, you know they smoked within the last two to three hours,” Lynn said.

But Hound Labs has focused on tests for those who have smoked pot, not those who have eaten it. That’s next on the list for development.

“We think the similar technology with some modifications will be able to detect edibles, as well, but we’re going to have to explore it,” he said.

Scientists also are trying to determine how marijuana affects driving performance. There’s not a lot of research available.

Andrew Spurgin worked on a 2015 study at the University of Iowa’s National Advanced Driving Simulator that found those who smoked marijuana before driving weaved more in their lane.

“We didn’t find an increased number of people weaving outside their lane, per se,” Spurgin said. “Really, what this points to is a decrease of control in ability to be very accurate in how you steer your car.”

The study did not add other road hazards such as drivers slamming their brakes or deer jumping in front of cars.

“What would happen in a situation where everything hits the fan and you have to do some thinking and some fast acting?” Spurgin said. “That’s one of the many questions still to be explored in the research going forward.”

Although there is a steep learning curve, Colorado highway officials are more aggressive in their enforcement and in delivering the message that driving high is a bad idea, Davis said.

CDOT created a car that fills with smoke as if people are toking inside. It draws attention, and once the smoke clears a message appears warning that stoned drivers will be charged with DUI.

The car is parked at festivals and other big events.

Officials want people to understand that driving after smoking weed is just as dangerous as driving after drinking, Davis said.

“We don’t take a position if you smoke or not,” he said. “Driving impaired by anything is still bad.”

As legalization spreads across the country, the federal government needs to get involved in setting standards, Davis said. For now, though, Colorado is the leader in figuring out how to prevent stoned driving and how to deal with those who do, he said.

“People for years are going to look to Colorado and ask, ‘What have you guys learned?'” Davis said. “We’re trying to get a handle on it so it doesn’t become a problem.”

Noelle Phillips: 303-954-1661, nphillips@denverpost.com or @Noelle_Phillips